By Heather Kuttai

By Heather Kuttai

“Tansi kakithaw niwahkomakinak.

Hello, all my relatives…

We can live any story we want.”

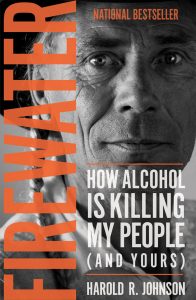

This is the tenet of Harold Johnson’s book, Firewater: How Alcohol Is Killing My People (and Yours). Generally, when writing a book review, it is considered best practice to focus on the book and avoid writing about the author. Yet, at the end of Aboriginal Storytelling Month, and after having lost Johnson, one of Saskatchewan’s best storytellers, I find that I cannot separate the two.

Harold Johnson was a prolific storyteller and a pillar of the Saskatchewan Indigenous community. He wrote 11 books; Firewater is arguably his most successful, as a national bestseller and shortlisted for a Governor General’s award. From his perspective as a Crown prosecutor, lawyer, and a Woodland Treaty 6 Cree man who is also well-accustomed to living off the grid, Johnson, who had a Masters of Law from Harvard, makes a passionate case for changing the story Indigenous people have been told for generations about the “lazy drunken Indian” and how the time is well overdue to re-write that narrative. However, he asserted that the people who must make this transformation are the individuals who are themselves addicted to alcohol, for their own sake, and for that of the future generations.

For this, Johnson has been criticized. Challenging people to acknowledge and ultimately, end the destructive power alcohol has over their lives and communities can appear victim blaming and it may be that Johnson did not give enough weight in Firewater to the systemic forces of racism, poverty, and intergenerational trauma in his calls to action. The strength of his book, however, is in the assertion that we are all the authors of our own lives and the power for change is in the connectedness to the land and whole communities – keys, he said, to healing, recovery, and hope for a strong future. His is a vision of whole communities coming together to serve as treatment centres rather than rely on the current social agencies that continue to perpetrate the self-defeating, victimizing, and disempowered narrative.

“My dream is that instead of sending our people away for treatment, we turn our communities into treatment centres … I imagine a future for our children and grandchildren, a healthy place where we are not experiencing the cycles of trauma and grief and drinking to overcome the grief, leading to more trauma. We get to that imagined future by changing the story that we tell ourselves and each other.”

Firewater is a book that exposes alcoholism in ways our society, as a whole, is reluctant to address, and it also offers solutions and hope for ways to, as Johnson said, “live a good life.” His visionary leadership and storytelling will be missed.