Several years ago, the Commission began hearing concerns from the public regarding the practice of police street checks. The Commission heard from people who believed street checks were discriminatory on the basis of race and other grounds protected under The Saskatchewan Human Rights Code, 2018. At the same time, several high-profile reviews of street check policies and practices were underway in other jurisdictions throughout Canada.

Recognizing the complexity of balancing the need to maintain public safety and the need for the public to be free from discriminatory interference, the Commission launched a systemic initiative designed to consider contact interviews with in the context of human rights.

For this review, the Commission conducted research and consulted police services throughout the province, the Saskatchewan Police Commission, numerous community-based organizations, and other stakeholders. The Commission considers this work to be the beginning of a process of improvement. Further collective efforts are required in order to effectively addressed the issues outlined in the report.

For more information about this initiative, contact [email protected]

1. Chief Commissioner’s Message

Police are entrusted by civil society with keeping order and fostering public safety. Accordingly, there are thousands of police-civilian interactions across Saskatchewan daily. Historically, one such type of interaction is a street check – referred to as a “contact interview” in Saskatchewan since 2018. These interactions involve the stopping of a person or persons by police for the purposes of obtaining information not related to the investigation of a crime.

Several years ago, the Saskatchewan Human Rights Commission began hearing concerns from the public regarding the practice of police street checks. The Commission heard from people who believed they were discriminatory on the basis of race and other protected characteristics. At the same time, several high-profile reviews of street check policies and practices were underway in other Canadian jurisdictions, such as the Independent Street Checks Review in Ontario, Dr. Scot Wortley’s report for the Nova Scotia Human Rights Commission, and the Review of the RCMP’s Policies and Procedures Regarding Street Checks.

There has been confusion and debate over the term “street check”, as well as what precisely constitutes a street check. In 2018, the Saskatchewan Police Commission released a new policy giving police clearer direction on the lawful use of street checks. This new “contact interview” policy gave the Commission a further opportunity to review the practice through a human rights lens

The Commission thanks the following people and organizations for their participation in this review:

- Professors Julie Kaye, Scott Thompson, and Glen Luther and their research teams

- The Saskatchewan Police Commission and Saskatchewan Police College

- Polices services across Saskatchewan, including those in Saskatoon, Regina, Estevan, Moose Jaw, Prince Albert, Corman Park, and Weyburn

- The Federation of Sovereign Indigenous Nations

- The Métis Nation of Saskatchewan

- Elizabeth Fry Society of Saskatchewan, John Howard Society of Saskatchewan, CLASSIC, OUTSaskatoon, Prairie Harm Reduction, chokecherry studios, Saskatchewan Intercultural Association

- The City of Saskatoon

The Commission is committed to continuing to work with stakeholder groups regarding contact interviews and other police policies in Saskatchewan.

Barry E. Wilcox, K.C.

Interim Chief Commissioner

Saskatchewan Human Rights Commission

1. Introduction

A Note on Terminology

The police practice commonly known as “street checks” sometimes goes by other names, including “carding,” “police stop,” “community contacts,” “stop and frisk,” and “stop and search.” While these terms are often conflated or used as synonyms for “street checks”, there are differences between each of the practices described by these terms.

In 2018, the Saskatchewan Police Commission (“SPC”) adopted a policy that provided guidance to police services regarding the proper conduct of a street check under the name “contact interview.” See Appendix 1 for the full SPC contact interview policy.

Accordingly, the term “contact interview” is used in this report when referring to these interactions within the Saskatchewan context.

When referring to the practice of police stopping a person for the purposes of obtaining and recording information not related to the investigation of a crime in other jurisdictions in Canada, in the Legal Analysis section of this report, and in some direct quotations the term “street checks” will be used.

This report refrains from using the term “carding” or other terminology where possible as they have various and conflicting understandings. However, these terms may be used when quoting other reports or community groups.

Background

News reports from across Canada suggest that the relationship between police and the public in some jurisdictions has been strained through polarizing events and grating day-to-day interactions.1 This has been especially noted by racialized communities.2 Academic research, case law, and news stories document that poor police-community relations are exacerbated by several factors, including history, poverty, social exclusion, and systemic racism.

While recognizing that “race” is a social construct that does not exist scientifically, racialization – and therefore the experience of racism – exists in societies.3 Racialization refers to “the process by which societies construct races as real, different and unequal in ways that matters to economic, political and social life.”4 While all people may be described as racialized, the term “racialized people” is used in this report to refer generally to people who are not White or Indigenous. Indigenous peoples may not define themselves as racial groups, but rather as peoples or nations.5

Concerns have been raised regarding police-community relations across Canada,6 including Saskatchewan.7 There are long-standing concerns in this country that street checks employ racial profiling and disproportionately affect those living in poverty and/or experiencing homelessness. There have been reports of street checks being carried out based on racial considerations, and an over-representation of Indigenous peoples and racialized communities in street checks.8

In the past five years, governments, commissions, and police boards across Canada have reviewed the practice of street checks as it relates to systemic discrimination and human rights. Several reports discussed in this report show that street checks disproportionately impact people according to race or socioeconomic status. Justice Tulloch reviewed Ontario policy, practice, and legislation and recommended amendments to regulations governing street checks.9 Griffiths, Montgomery, and Murphy were commissioned by both the Edmonton Police Commission and later the Vancouver Police Board to review research, interview community stakeholders, make findings, and provide recommendations. All recommended that if police continue to use street checks, the public should be consulted and educated. It was also recommended that the use of street checks should be monitored and data reported regularly.10 Scot Wortley, reviewing street checks practice and policy in Halifax, recommended the practice be discontinued or better regulated.11

Public perceptions about the nature and value of street checks often depends on lived experience, community experience, and history. For Black12 communities, street checks have historical linkages to “the practice of the issuance and mandatory enforcement of slave passes.”13 For Indigenous communities, the police practice of street checks has been likened to the historic pass system instituted by the federal government.14

Relations between the police and Indigenous peoples in Canada have been fraught with conflict from the beginning of policing in Canada. Indigenous communities say they are over-policed, and that officers may carry prejudice and discriminate based on race, which leads to unfair treatment and over-incarceration, as well as fear and distrust of police.

Over the last few years, global events, such as the Black Lives Matter movement, have had local implications and have accelerated public dialogue and concern about police-community interaction and the impact on the safety of racialized and marginalized persons.

Legal scholars and academics have analyzed street checks with the aim of providing an understanding of the impact of policing and suggesting how to bridge the divide between communities that feel over-policed and under-protected, and police services that are managing multiple competing interests and responsibilities.

One connective thread through all these issues is the statutory prohibitions on discrimination found in human rights legislation.

The Saskatchewan Human Rights Code, 2018

The Saskatchewan Human Rights Code, 2018 (the “Code”) provides for the protection of the human rights of all people in Saskatchewan and prohibits discrimination against any individual in social areas of life such as in housing, education, employment, and services (which includes policing). The Code is quasi-constitutional in nature and has primacy over all laws in Saskatchewan, except where specifically excluded by legislation.

Personal characteristics are referred to as “prohibited grounds” under subsection 2(1) of the Code, and include but are not limited to: age, disability, race or perceived race, colour, ancestry, place of origin, receipt of public assistance, sex, gender identity, and sexual orientation.

Prohibited grounds cannot be used as a basis to deny access or services to, and/or adversely target specific groups or individuals.

The Saskatchewan Human Rights Commission administers the Code. Its mandate is to promote and protect the individual dignity, fundamental freedoms, and equal rights of Saskatchewan residents. The Commission’s role includes promoting measures that prevent and address systemic patterns of discrimination. It is within the authority of the Commission to review police policy as it relates to human rights.

Conducting a contact interview based on an individual’s prohibited grounds may be discriminatory under the Code.

Discrimination is any unfair action, policy, or practice that puts a person or group at a disadvantage by treating them differently from others. Discrimination can also occur when important personal differences or needs are ignored, resulting in a person or group being unjustly denied opportunities or receiving fewer benefits.

Sometimes discrimination is deliberate and direct – such as the use of racial slurs or refusal to employ someone because of their race – but it can also be indirect or unintentional. In these cases, discrimination can flow from prejudice, negative stereotypes, or a failure to consider the needs of others.

Contact interviews also engage the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms protections against unlawful arrest, restriction of liberty, unlawful detention, and unlawful search and seizure.15 Police have statutory and common law powers to enforce law and order in a democratic society and must, at the same time, refrain from violating human rights and Charter rights.

Systemic Approach

The Commission’s systemic initiatives seek to examine the processes (policies, procedures, and practices – both official and informal) that may contribute to unfair disparities and discrimination. Once problematic processes are identified, they can be reviewed and revised as required to eliminate and remedy inequity and other barriers. Such an examination also highlights existing positive processes and notes past successes.

Recognizing the complexity of balancing the need to maintain public safety and the need for the public to be free from discriminatory interference, the Commission set out to consider the contact interview policy and practice from a human rights perspective. As with other systemic initiatives, the Commission sought out stakeholder perspectives through interviews, meetings, and submitted documents.

Three interconnected goals shaped the focus of this systemic initiative:

- To review research, case law, and stakeholder perspectives on the policy, purpose, and practice of contact interview.

- To determine whether the current contact interview policy complies with the provisions of the Code,

- To engage with stakeholders who are involved with the implementation of the policy and/or who can speak to the impact of the policy, with the goal of identifying challenges and unresolved issues.

2. Saskatchewan Contact Interview Policy

The Saskatchewan Police Commission

The SPC provides oversight of the training and operation of municipal and First Nations police services in Saskatchewan, including: Regina, Saskatoon, Moose Jaw, Prince Albert, Estevan, Weyburn, Dalmeny, Luseland, Corman Park, Vanscoy, Wilton, and File Hills.

The mandate of the SPC is assigned at subsection 19(1) of The Police Act, 1990.16

Duty and powers of commission 19(1) The commission shall promote:

- adequate and effective policing throughout Saskatchewan; and

- the preservation of peace, the prevention of crime, the efficiency of police services and the improvement of police relationships with communities within Saskatchewan.

The SPC publishes a Policy Manual for Saskatchewan Municipal Police Services (the “Policy Manual”) pursuant to section 19(2)g of The Police Act. Its purpose is to provide direction to municipal and First Nations police services to ensure consistency throughout the province.17 The Policy Manual provides a minimum standard that each police service is required to meet with written procedures that are accessible to the public.

SPC Contact Interview Policy

The SPC developed a contact interview policy amid community concerns over street checks in Saskatchewan.18 The policy was adopted in May 2018 (see Appendix 1 for a full copy of this policy). 19 In November 2018, the SPC released a training video and explanation of the policy to all operational police officers.

The SPC engaged in a dialogue with the Commission about the content of the policy and its effect on police-community relations.

The SPC defines a contact interview as “a contact with the public initiated by a member of a police service with the intention of gathering information not related to a specific known incident or offence.” The information being sought must be more than general information common to the community, and the policy specifically excludes: normal social interactions; undercover activity; purely visual observations; circumstances where investigative detention is authorized; and, situations where specific statutory authority is used, such as stops and checks under The Traffic Safety Act or other legislation.

The policy emphasizes that contact interviews must be performed in a manner that respects

Charter and human rights and must not be conducted on a random or arbitrary basis.20 The policy further elaborates:

“Contact interviews are appropriately conducted by members only where the subject’s behaviour or the circumstances of the contact cause the member to have a concern as to the subject’s purpose or for the subject’s safety. Circumstances which should be considered and which may give rise to a concern would include:

- there is no apparent reason for the subject’s presence in a particular area, such as being present in a commercial or industrial area late at night when everything in the area is closed;

- the subject’s actions, behaviour or demeanor raise a concern as to his/her purpose or for his/her safety; or

- the subject appears to be lost, confused, frightened or in need of

In the absence of actions, behaviour, demeanor or circumstances giving cause for concern as set out above, contact interviews may not be conducted based solely on the subject’s:

- location in an area known to experience high levels of criminal activity and/ or victimization;

- actual or perceived race, ethnicity or national origin;

- colour;

- religion;

- age;

- gender, gender identity or sexual orientation;

- physical or intellectual disability or impairment;

- mental disorder;

- any other ground of discrimination prohibited at law;

- socio-economic circumstances;

- medical condition; or

- other personal characteristic of a similar nature. ”21

The SPC’s chair has emphasized the need to avoid racial profiling, saying: “Stopping someone because of some identifiable characteristic that’s protected under the Human Rights Code, including race, would be improper.”22 The policy lists several personal characteristics (above) that are protected grounds prohibited from discrimination by the Code, including race.

Policy Language

The policy states that contact interviews may not be conducted based solely on a person’s prohibited grounds. The current wording of the policy leaves open the possibility that a prohibited ground may be one of the reasons a police officer conducts a contact interview. Depending on the circumstances, this is potentially discriminatory under human rights law.

The initial portion of the definition of a contact interview appears to leave open the use for purely intelligence-gathering purposes (“ … gathering information not related to a specific known incident or offence”). However, the policy then appears to restrict the use of contact interviews further, stating that contact interviews are “appropriately conducted by members only [emphasis added] where” there is “a concern as to the subject’s purpose or for the subject’s safety.”23

Police Services Policies

Municipal police services in Saskatchewan have adopted the SPC contact interview policy in their own policy manuals. While the policies share the majority of the same wording as the original SPC policy, contact interview polices vary slightly from service to service.

Like the SPC policy, the Regina Police Service and Prince Albert Police Service policies state that a contact interview does not include officer interactions with an individual without cause for concern, such as in normal social interaction or general conversation with the public. The Saskatoon Police Service policy does not make clear mention of this.

However, the Saskatoon Police Service policy provides more specific instruction to its police officers on what type of information may be collected from a person during a contact interview, including:

- Date, time, and location of contact;

- Identification and contact information of the subject and/or a physical description;

- Duration of contact;

- Vehicle description (license plate, permit number, ); and

- Other information relevant to the nature of the contact and member’s 24

The SPC policy allows for a broad range of information that could or should be recorded by officers. It states that information will vary depending on the nature of the contact and the officer’s concern. It also states that officers must use judgment and discretion in collecting information and must only collect what is necessary to address their concerns related to the subject’s purpose or safety. This level of discretion could lead to differential treatment of the public and could lead to complaints of discrimination on the basis of a prohibited ground.

The SPC policy states that information obtained during contact interviews should be recorded in the officer’s notebook and entered in the police service records management systems in accordance with the police service policy. The information is to be retained in accordance with the police service policy and destroyed after five years. The information is only to be accessed by officers during the conduct of lawful investigations or for the purposes of collecting statistics for reporting to the SPC.

Statisics and Complaince

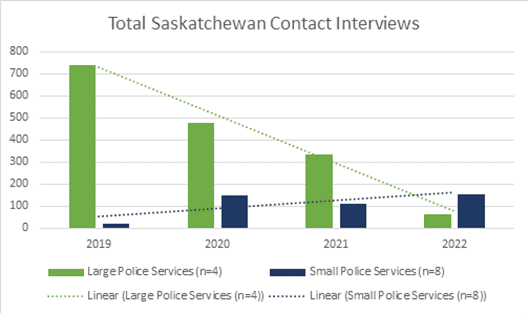

The SPC contact interview policy (OC 1509) requires that police services submit annual reports about their use of contact interviews. These reports were reviewed by the Saskatchewan Human Rights Commission. The data is depicted in the chart and graph below.

| Annual Contact Interviews25 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

| Large Police Services (n=4) |

740 |

476 |

335 |

61 |

| Small Police Services (n=8) |

21 |

147 |

108 |

155 |

| Grand Total: | 761 | 623 | 443 | 216 |

The annual reporting requirement began in 2018. However, according to the SPC, some police services took a reasonable amount of time to formalize and introduce their own local contact interview policies and, as such, many began reporting only after 2019.26

In 2019, the Saskatoon Police Service and the Prince Albert Police Service initially reported the highest use of contact interviews (201 and 497 respectively). The overall decline in the number of contact interviews is largely due to the reduction over the subsequent years at these two police services. In 2022, the Saskatoon Police Service reported just 16 contact interviews, while the Prince Albert Police Service reported 37.

At the same time, the reports from smaller police services in Saskatchewan show more contact interviews being conducted.

The SPC noted that there are improvements to be made in the consistency and quality of reporting from the police services, and that it intends to prioritize this as an upcoming issue. The SPC also intends to audit and review of the practices within each police service, and to determine how the process can be improved to become more accurate and effective in the future.27

3. Legal Analysis

The Definitions of Street Checks

There are differing understandings among the public and within police services about what constitutes a street check, contact interview, or carding.28 Confusion may arise because the terms are sometimes used interchangeably by police services and the community, while sometimes the terms are understood to have different meanings.

In R v K(A), the Ontario Court of Justice defined street checks as a “practice involving stops of citizens by police, whether there is an offence being committed or not, and recording the contact and personal information about the citizen.”29

However, the British Columbia Civil Liberties Association defines street checks as:

… the practice of stopping a person outside of an investigation, questioning them and obtaining their identifying information, and often recording their personal information.30

Similarly, Justice Michael Tulloch defined street checks as an inquiry for, and capture of, “identifying information obtained by a police officer concerning an individual, outside of a police station, that is not part of an investigation.”31

Generally, a street check refers to police interaction with a member of the public for the purposes of gathering information that is neither part of an ongoing investigation nor a mere social interaction.

The data collected during a street check is stored in police data management software. Police might then use it for various purposes.

In Saskatchewan, since 2018, the practice of street checks has been subject to regulation and has been specifically defined as a “contact interview,” and means: “a contact with the public initiated by a member of a police service with the intention of gathering information not related to a specific known incident or offence.”32

Statutory and Common Law Authority for Policing and Detention

Provincial or federal legislation and common law provide legal authority for police powers. There are no provincial or federal statutory provisions that specifically empower police to carry out contact interviews in Saskatchewan; individual police service policies govern the use and procedures of contact interviews.33 Since 2018, the SPC has provided specific procedural direction to police services regarding contact interviews.

Municipal police services derive their authority from provincial legislation. In Saskatchewan, the primary legislation from which municipal police derive their powers is The Police Act, 1990,34 which states that the police have the power and responsibility for “preservation of peace,” “the prevention of crime” against laws in force, and the “apprehension of criminals, offenders who may be lawfully taken into custody.”35

Through the Provincial Police Service Agreement, Saskatchewan contracts Royal Canadian Mounted Police (“RCMP”) to provide policing services to a number of municipalities and First Nation communities across the province. The RCMP is also subject to federal legislation, which empowers them to “perform all duties that are assigned to peace officers in relation to the preservation of the peace, the prevention of crime and of offences against the laws of Canada and the laws in force in any province in which they may be employed, and the apprehension of criminals and offenders and others who may be lawfully taken into custody.”36

The Criminal Code of Canada establishes clear police authority to arrest individuals.37 The courts have recognized that the principal duties of police officers are “the preservation of peace, the prevention of crime, and the protection of life and property.”38 Police also have the common law duty to solve crimes and bring perpetrators to justice.39 However, these powers are tempered by individual rights and freedoms and common law requirements. Police “are not empowered to undertake any and all action in the exercise of that duty” because “individual liberty interests are fundamental to the Canadian constitutional order.”40

Every person in Canada possesses fundamental rights and freedoms guaranteed under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (the “Charter”) 41. Youth have further protections related to criminal justice under the Youth Criminal Justice Act.42 Police officers must exercise their statutory or common law duties within the limits of the law. The Supreme Court of Canada has consistently ruled that unlawful police action against an individual (such as unlawful arrest, detention, search, and seizure) amounts to a breach of a person’s Charter rights. Furthermore, laws themselves must ultimately comply with the rights and freedoms guaranteed under the Charter. Laws that unreasonably restrict rights and freedoms will be deemed unconstitutional by courts.

Charter rights which may be directly affected during and after a contact interview include: the freedom of peaceful assembly and association; right to life, liberty, and security of the person; freedom from unreasonable search or seizure; freedom from arbitrary arrest, detention, or imprisonment; and, sometimes, a person’s rights upon detention.43

Police do not have a general right to detain people for questioning (i.e., prevent them from walking away) unless there are reasonable grounds to suspect that the person is connected to a particular recent or ongoing crime and the detention is reasonably necessary with an objective view of the circumstances.44 A mere suspicion, intuition, or “hunch” that someone might be doing something illegal, or a vague concern for safety, is not enough to meet the requirement of suspicion based on reasonable grounds.45 Something more is required because “subjectively based assessments can too easily mask discriminatory conduct based on irrelevant factors such as the detainee’s sex, colour, age, ethnic origin or sexual orientation.”46 A police officer’s intuition in detecting crime “should not be based on a person’s physical characteristics, unless those physical characteristics match a suspect’s description or a relevant in some other appropriate way.”47

An officer must be able to show articulable and justifiable cause for detainment. There must be “a constellation of objectively discernible facts which give the detaining officer reasonable cause to suspect that the detainee is criminally implicated in the activity under investigation.”48 Again: the Charter explicitly protects against arbitrary detentions. If police detain a person without reasonable grounds for the stop, this violates the person’s rights, and is unlawful.49

However, not every police interaction constitutes detention. While any police interaction may involve “delays” or waiting, the protective sections 9 and 10 (right to counsel and reason for their detention) of the Charter are not e9ngaged by delays that do not involve significant physical or psychological restraint.50 The point at which a police interaction crystallizes into a detention depends on the facts surrounding the interaction, including the police conduct and circumstances of the individual.

Canadian jurisprudence recognizes that detention can be physical restraint or psychological restraint. When physically restrained by a peace officer, a person is detained. Whereas psychological detention “is established either where the individual has a legal obligation to comply with the restrictive request or demand, or a reasonable person would conclude by reason of the state conduct that he or she had no choice but to comply.”51

If police detain a person for investigative purposes, the officer must recite the police cautions. The reasons for the detention must be advised in clear and simple language52 and the person being detained must be informed of their right to seek counsel. The person does not have to speak to the police. Individuals have the right to remain silent when approached by police.53 Moreover, the detention should be brief in duration, and not prolonged unduly or artificially.54

During police interactions without physical restraint, but in which a person believes they have no choice but to do as the officer says, a psychological detention may occur. Such a detention will trigger the Charter rights to be informed of their right to counsel and the reason for their detention.55 The test to determine whether a psychological detention has occurred involves an objective evaluation of all the circumstances of the encounter and the police conduct, from the perspective a reasonable person in the individual’s circumstances.56 Put another way, the test asks whether the conduct of police “would cause a reasonable person to conclude that he or she no longer had the freedom to choose whether or not to cooperate with the police.”57

Numerous factors may lead some people to feel they are required to obey a police officer who asks them to stop and identify themselves. These factors include, but are not limited to: racial identity,58 young age, lack of sophistication, lower intelligence, and emotional disturbance.59

Courts have recognized that racialized people, because of background and past experience, may feel especially unable to disregard police orders because of a concern that “their right to walk away will itself be taken as evasive and later be argued by the police to constitute sufficient grounds of suspicion to justify a … detention”60 and so they may “more readily submit to police demands in order to move on with their daily lives because of a sense of learned helplessness.”61

To avoid any question of psychological detention and voluntariness, courts have indicated that police can tell people that they are not required to answer the questions and that they are free to leave.62

What Constitutes a Lawful Contact Interview

There is no law that compels a person to participate in contact interviews conducted by police.63 A person can walk away and does not have to identify themselves.64 A contact interview is, by definition, a voluntary interaction. The police cannot compel a person to remain stopped if there is no arrest or detention.

For a contact interview to be a constitutional and lawful police action it must be: voluntary (and not constitute a detention); not arbitrary or random; and, not discriminatory under human rights legislation.

An improperly conducted contact interview may constitute unlawful detention, discrimination under human rights law, or potentially both.

However, some community advocates and legal academics argue that contact interviews cannot ever be truly voluntary for racialized communities or youth.

The Supreme Court of Canada has described the impact of over-policing in racialized communities to be more than an inconvenience: it takes a toll on a person’s physical and mental health.65 The Court stated that carding and over-policing contribute to the social exclusion of racial minorities, increases distrust in fairness of justice system, and perpetuates criminalization.66

Nevertheless, while the Court has recognized that the experiences of racialized persons is a factor in determining whether (psychological) detention exists,67 the Court has not determined that contact interviews (or street checks more generally), in themselves, constitute detention.

4. Saskatchewan Police and Contact Interviews

Police Views on Contact Interviews

To gain a better understanding of how contact interviews are perceived and applied, the Commission interviewed representatives from several police services in Saskatchewan, including Chiefs of Police, Deputy Chiefs, Sergeants, and a cultural coordinator. Their comments are described in this section, along with select quotations.

Contact Interviews as a Policing Tool

In Saskatchewan, each police service the Commission interviewed placed a different value on contact interviews.

Urban police services such as Prince Albert, Regina, and Saskatoon tended to view contact interviews as a useful intelligence gathering tool that can contribute to public safety.

Representatives from these police services explained that when used correctly, with reasonable cause or suspicion, contact interviews may help prevent crime. One police participant suggested that contact interviews could help get guns and other weapons off the streets.68 Others noted that contact interviews might prevent thefts or property damage in areas where those crimes are trending.

Smaller police services, on the other hand, found less crime prevention value in contact interviews.

[There is a] different context in a small town. It’s easier to recognize someone who is not from the community because everyone knows everyone. I don’t think [contact interviews] provide the same value … Outside of an investigative purpose, [they] don’t provide a lot of value [here].69

I don’t see a great amount of usefulness [in contact interviews]. If there is a question of infringing on people’s rights for a valued [crime prevention] outcome, I just don’t see it.70

While the perceived benefits of contact interviews as a crime-solving tool may vary from service to service, police throughout the province said that contact interviews can be a useful tool for community interaction.

It’s a lot of rapport building. Just trying to bridge the gap by having a basic conversation. Relationship building is definitely one of the intentions of contact interviews, street checks, without a known incident or offence. That is one intention.71

The Saskatoon Police Service’s policy states that contact interviews are a valuable tool for community engagement, community safety, and crime prevention and solving.72 It also states that the policy provides guidance to police so they can build rapport through their approach, demeanor, and communication skills.73

Community policing is referenced in the first paragraph of the SPC policy:

“The public expect members of a police service to engage with the people of the communities they provide service to, to become familiar with the community and its residents and to continuously communicate with them. For that reason, police services throughout Saskatchewan and the Saskatchewan Police Commission remain committed to Community Policing as their approach to serving our communities effectively.”74

Police value casual and social conversation between police and community members, and do not want that to stop. The idea that interactions between police and community promote safety is a common reason police support contact interviews. However, as previously noted, a casual social conversation where no identifying information is shared or recorded is not a contact interview and would not be recorded as such.

A couple of police services reported that most of the public interactions they are involved in stem from calls regarding property crime or responding to someone on the side of the road and, therefore, do not meet the criteria in the contact interview policy. People involved in these types of interactions may be asked for their name or information about what they are doing, what they have seen, or whether they are physically well, but it will not be recorded as a contact interview.

Implementatoin of SPC Policy and Public Concerns about Contact Interviews

During the course of the interview process, many police representatives told the Commission that the SPC contact interview policy has been implemented properly and, as a result, there have been few complaints regarding the policy.

Our board surveyed the community and found support of the policy. We also do community engagement sessions and have had no concerns brought forward about the policy.75

I am not aware of any concerns or complaints in 15 years.76

Some suggested that while the policy itself can be beneficial, there is need for more equitable frontline implementation of contact interviews.

[They] are beneficial to community safety, beneficial to the police, the community. Definitely not beneficial to young, non-Caucasian men. Not beneficial to them. Not beneficial to areas with low economic status … We know that marginalized people are overrepresented in the justice system and street checks have contributed to that through racial profiling. We are not debating that. If someone is debating that, they are 10 years behind.77

Implementation of SPC Policy and Public Concern about Contact Interviews

Police services throughout Saskatchewan are aware of the concerns surrounding street checks in Canada. They understand that street checks have been subjected to public scrutiny that has resulted in procedure reviews, policy changes and, in Nova Scotia’s case, a permanent ban.

Many police representatives didn’t feel as though an outright ban of contact interviews in Saskatchewan would be a prudent course of action.

Banning of [, in my view, is the sile9ncing and stifling of respectful conversation that can, and should, happen between police and people in the community.78

No [there shouldn’t be an] outright ban because people must be part of the police and police must be a part of the people.79

Others were more ambivalent towards the idea of a ban.

I don’t think an outright ban would necessarily lead to an increase in crime or anything like that. The world would not come to an end because we can’t ask a name at 2:00 a.m. I think it might just stifle normal interaction with someone

… In the research I have done I don’t think anyone has made the case in a logical manner that outlawing these things would create a huge crime burst in the country.80

Multiple officers involved in police interviews suggested that the public may have misconceptions about contact interviews. They expressed concern that the perception might exist that contact interviews are the same as carding, and that police are simply engaging in the same practice under a different name.

A few of the veteran police participants acknowledged they had been trained to use vagrancy cards earlier in their careers. None supported the practice,81 which they describe as randomly or arbitrarily approaching a person on the street based on a personal protected characteristic, obtaining identifying information from that person and storing those details in a police database.

We started to recognize that a lot of those street checks had fairly significant racial bias. We saw then that predominately they would be checking the ladies working the street corners … Sometimes it has a positive impact when people go missing, sometimes it helps with crime, or who is out at 3 a.m. But we have to go back and look at those things and see that they had a significant racial bias.”82

Carding, to me, should not happen in society in Canada. Ever. Arbitrary collecting of data to keep an eye on the community has no merit and should not exist.83

The term “carding” came from a historical police practice of writing down information from interactions on small paper index “vagrancy” cards. If there was subsequently a crime in the area, police would go through the cards to see who was in the area and try to determine if the individual may be able to provide information or if they may be a suspect.84 The practice of carding is no longer in use in Saskatchewan.

Potential Improvements to Contact Interviews

During each interview, police representatives were asked how contact interviewing could be improved in Saskatchewan. One of the main recommendations was to provide more training for police officers.

One officer suggested the focus should be on addressing bias in police services and providing training to eradicate it.85 Another officer felt the solution was to focus on training compassionate officers to carry out contact interviews eth9ically, according to sound policy, using body cameras, and with civilian oversight and review.86

Many police representatives interviewed by the Commission agreed with the need for more ethical and empathetic training for officers throughout the province.

There is a significant need for it. Through all levels of the organization. Not just for junior constables … [we need to] create space for social awareness, emotional intelligence, and an understanding of social issues. 87

I think training is lacking. Euphemistically, we will teach you 99 ways to kills people, but not to treat them with dignity and respect. I think we need to spend a little more time … dealing with human rights, treating people as individuals.88

One of the issues is: we teach young people how to do arrests, how to read rights, how to do many things, but my concern is there is a big shortage about teaching them common sense and training them how to treat people like people.89

Another common recommendation was the need for police services in Saskatchewan to implement measures that improve relationships, enhance trust, and better address community needs.

These measures could include recruiting differently.

Right now, policing is choosing the best of the best. The fastest runner, the strongest, the smartest. That’s not what the community needs. They need compassion, not judgement … You don’t need alpha males. You need compassionate officers who, if they lose an intellectual battle on the street, don’t react.90

You need to [recruit and] hire people with lived experience.91

The organization does not reflect the community it serves. That’s the issue … [Indigenous people are] overrepresented in [contact interviews] and underrepresented in employees conducting the checks … Specific police services have dismantled barriers in place locally for their own organization, but provincially we are still handcuffed to an archaic plethora of barriers.92

It could also mean a deeper, more meaningful commitment to community policing.

Police need to evolve with what the community expects. If mental health and wellness is part of that, then they have to … work at it. Partner with health [professionals and organizations]. Community policing is responsive to community needs.93

It goes back to community policing. Luxury of walking beat for many years and as a result of that I had the luxury of being able to sit down with “hookers” for a milkshake, talk to them … We have to change our own mindset. Figure out how to change the mind of police officers and have the emotional intelligence to deal with people. We have to do enforcement, but also have to do empathy … You cannot arrest your way out of societal problems. Will not arrest your way out of mental heal9th and addictions issues. I think police and organizations are finally realizing that, but we have a long way to go.94

5. Community Views on Contact Interviews

To understand community perceptions about contact interviews, the Commission spoke with numerous Saskatoon-based stakeholders in 2022. The information they provided offered a valuable glimpse into the perspective of lived experience. It must be noted that a number of anecdotes about police interactions offered to the Commission did not constitute contact interviews.

The community stakeholders interviewed by the Commission held a variety of opinions about policing. Some community groups and citizens express support for the contact interview policy. However, this section contains only the most specific critiques about contact interviews or other police practices.

Interview participants consisted of advocates and representatives from community-based organizations including CLASSIC, OUTSaskatoon, Prairie Harm Reduction, chokecherry studios, the Saskatoon Intercultural Association, the Elizabeth Fry Society of Saskatchewan, the John Howard Society of Saskatchewan, the Federation of Sovereign Indigenous Nations, and the Métis Nation of Saskatchewan.

In general, the public’s understanding of contact interviews differs from that of police.95 While police may assert contact interviews are a tool of intelligence gathering and community policing, the people who experience contact interviews often say they are a tool of racial profiling, intimidation, and discrimination.

Participants described a typical contact interview scenario in which police will approach individuals walking or bicycling and ask for their name and an explanation of what they are doing or where they are going. Police will then run the individual’s name to check for outstanding warrants or if the individual has conditions related to release from prison. If the person has family members who are in a gang, or if they are affiliated with a gang themselves, police will often ask for information regarding gang members. Police may also ask individuals if they know the whereabouts of a missing person from the community.96

A person may be stopped because they have been seen with a gang member in the past, which could be a family member or a friend.97 Individuals who are known to police and/or have a longer criminal record are likely to be stopped more often.98

The unhoused or homeless population are particularly likely to be questioned by police.99 When it comes to those experiencing homelessness, extreme weather can be used as a premise for questioning people and then issuing tickets.100

A representative from one community-based organization told the Commission about a homeless client who was stopped by police and found to have a knife in his bag, which he used in the preparation of food. He was charged for carrying a concealed weapon, then a short time later was stopped for jaywalking.101

Another community organization suggested that if a person does not cooperate with sharing information, officers may threaten to report them for a breach of parole conditions, such as drug possession, use, or intoxication. The organization noted that this seems to happen most often when an individual has recently been released from prison and is living at a shelter and/or is experiencing homelessness.102

Transgender or gender non-conforming people may feel they are especially vulnerable to contact interviews and invasive questioning, particularly if their name and gender does not match the name and sex on their identification.103

Most stakeholders interviewed by the Commission noted that it appears young to middle-aged Indigenous or Indigenous-looking individuals in core neighbourhoods are more frequently subjected to contact interviews. One participant added that this is despite the fact that non- Indigenous people in similar circumstances occupy the same areas.104

An employee at one organization witnessed an Indigenous community member sitting on a bench reading a book then being approached by police and questioned. The employee noted that contact interviews need to happen for a better reason than someone “merely existing as an Indigenous person in public.” 105

For the most part, community organizations are of the opinion that police use more verbal aggression and intimidation towards Indigenous clients than non-Indigenous clients to get information about that person or someone police are looking for.106 Racialized individuals feel like police hope they are breaking the law or parole conditions so they can put them in prison.107

Power Imbalance and Detention

Stakeholders who participated in the Commission’s interview process often described contact interviews and other police-community interactions (including investigative detention)

interchangeably. This is important. Stakeholders report that many of the people they serve are uncertain as to why they are being approached by police. As a result, these people experience no qualitative difference between a contact interview and investigative detention, or other type of police stop.

Police are in a clear position of authority. Stakeholder organizations report that most community members believe they are detained whenever talking to a police officer and are required to do whatever police say. The power imbalance may be even greater when the individual is a young person or has lower cognitive abilities.108

There is a lack of awareness that participation in a contact interview is voluntary. A community organization interviewed by the Commission said that none of its clients who have been subjected to contact interviews knew their participation was voluntary.109

I‘ve had so many people who do not know what that when they are stopped they can say nothing and walk away. A lot of times, people feel bullied or intimidated into it. I have not had a single person that has been stopped that knew it was voluntary.110

One community representative, an Indigenous woman, told the Commission that she didn’t know until she started working for her organization that the police did not have the right to search her, get her name, or get her identification card during a contact interview. She had always operated under the assumption that you had to tell the police all your information.111

There is a perception that individuals who chose not to respond to police questioning are more likely to be detained by police for being obstructionist.112 For these reasons, racialized individuals say they will usually comply with police demands even though they know they do not have to, in order to avoid violence or arrest.

It should be noted that some organizations in Saskatchewan work to educate the community on their rights related to interactions with police. Several community representatives spoke about the helpful presentations and informational cards that CLASSIC provides.

Effects of Contact Interviews on the Community

Many organizations the Commission interviewed reported that their clients, and in some instances staff, feel like they are under constant surveillance by police. Persons from racialized communities often feel over-policed and over-monitored, as though they are being watched because of their race, because of where they live, or because of where they spend time.

Several organizations said that a general avoidance of police is common among their clients, particularly in the core neighbourhoods. A representative from one such organization reported a noticeable decrease in clients accessing their services when police are in the area or around the organization’s building.113

Many community representatives suggested that the cumulative effect of interactions with police is a reduction of trust in the police and an increase of fear of police. One participant told the Commission:

As an Indigenous person … there is a certain fear when I interact with police. A generational trauma kind of thing. A fear where I have to hold my breath they to come … to talk to me. Their questions are like I’m being interviewed or under a microscope. If I say the wrong thing, that will give them a reason to ask for my ID – even though I haven’t done anything. 114

Another participant was of the belief that discriminatory police action leads to more “institutional mistrust”115 which is particularly experienced by Indigenous community members who have current and historical reasons to distrust institutions, including police.

This distrust reduces the likelihood that community members will rely on police for support in an emergency,116 such as domestic violence situations or other life-threatening circumstances such as overdoses.117 In circumstances where community members are familiar with legislation such as the Good Samaritan Drug Overdose Act,118 they still don’t trust that they will not somehow become negatively involved in the justice system if they call for emergency services.119 Community members have concerns that police are not aware of the Good Samaritan Act, or if they are, do not understand it properly or choose not to respect it.

Other organizations located outside of the core areas had different experiences and perceptions when it came to newcomers. The concerns with police interactions related to where there may be a language barriers, cultural differences, and lack of understanding.120 There have been instances of newcomers getting charged for obstructing a peace officer because “they didn’t understand … they didn’t speak the language and [were] fleeing because they are afraid based on experiences from home.”121

These organizations had less familiarity with contact interviews and less feedback from clients related to this topic. There are various possibilities for this difference. It was noted that some newcomers and Indigenous clients are “not accustomed to … viewing the police as a system that they can turn to.”122

The over-arching theme that emerged from community interviews was that there was a significant disconnect between community and police, and that contact interviews may further fracture that relationship. The repair of this relationship is a community safety issue.

Community Observations of the Contact Interview Policy

Stakeholders did not perceive any substantive difference in how contact interviews are conducted since the adoption of the contact interview policy in 2018.123 Further, no noticeable changes in location, prevalence, or content of contact interviews, were identified. One organization noted that police presence has increased since the pandemic, especially in core areas.124

This perception is in contrast to a reduction in the number of contact interviews reported by police services. There are various factors that may explain this difference between experience and statistics. It may be related to limitations in awareness of what constitutes a contact interview.

When asked to comment specifically on the policy, none of the stakeholders had positive comments regarding the substance of the policy. Furthermore, several organizations suggested that the policy does not explicitly require police to communicate to the individual what a contact interview is, that it is voluntary, and when it stops being a contact interview and becomes something else (such as an investigation), despite the obligation to advise people when they become a suspect.125

The Saskatchewan Police Commission intends to audit and review contact interview practices in the province.

Improving the Police-Community Relationship

Participants interviewed by the Commission highlighted what they observed to be working well, and where they saw opportunity for improvement. Several Saskatoon-based community organizations, for example, highlighted positive relationships with the Community Mobilization Unit (“CMU”) of the Saskatoon Police Service. They attribute this to the different approach to community policing that the CMU follows. This small team of specialized officers are more trained in crisis and conflict de-escalation, take time to get to know the community, and are less judgmental and can help them access resources.126 Some organizations said they will call in the CMU to help clients in distress (if the client agrees) or to access services.127 Because the CMU has more pull to get someone a bed in a shelter or detoxification centre, organizations will ask them to help with that, though the CMU does not help with transport.128

One organization said it works with a police liaison officer from the gangs and guns unit that meets socially with youths at the group home. Although it is challenging to help previously incarcerated individuals who had violent apprehensions feel comfortable with police, they see value in building a relationship between police and young people.

In terms of suggestions for change, youths recommended focusing on pro-social actions such as rights education, life skills training, and access to safe houses or drop-in centres.129 They also suggested that police need enhanced training in de-escalation tactics and trauma.130

Other community interviews indicated the need for police to meaningfully engage in anti-racist, anti-oppressive, anti-violence, and anti-sexist practices.131 A consistent response from the community-based organizations was that police training and practice does not focus enough on de-escalation techniques, anti-racism, and anti-bias training.132 As such, interview participants emphasized the need for increased police training in de-escalation tactics in a trauma-informed manner.133

Community organizations point to the value of mutual respect. In conversations regarding police, participants – youth especially –describe how officers carry themselves and if they use accusatory and confrontational language.134 Community representatives report there are some officers who automatically assume a youth is doing something wrong, rather than humanizing the person.135 One organization suggested that “it would be reasonable for police to consider how they engage with youth. They are children in a lot of instances, and [police] have a very one size fits all approach when it comes to engaging community members.136

Another organization told the Commission that women police officers tend not to ask as aggressive questions as male police officers.137 Several community stakeholders believe that police should focus on individual police officers who are doing the right things and build on that.

There is a general sense that too much is being asked of police and their resources, when their primary role is to respond to and investigate crime.138 All stakeholders reported that social workers or other professionals with therapeutic training would be better suited to respond to mental health calls, wellness checks, or other calls that would require more de-escalation techniques to be used with vulnerable populations. They could also do more preventative work with the goal of stabilizing people, finding housing, and preventing their interactions with police or entrance into the criminal justice system.139 This would cost less than relying on police response and prison time. This would be outside of the policing environment, more like a community health support and response team. The volunteer Okihtcitawak Patrol Group in Saskatoon was an example of this type of non-uniformed community support work, but the group was not able to stay in operation.140

An Indigenous governance organization the Commission interviewed said that community policing needs to evolve with community needs. If community needs mental health and wellness support, then police need to partner with health supports to make that happen.141 It was also suggested that police need to reflect the community by hiring officers who have lived experience, such as family with addictions. First Nations self-administered policing models was suggested as a solution that could be trusted by its community because it is grounded in community and is not a military-style model.142

6. Thompson and Kaye Report

The practice of street checks has been widely studied in Canada. This report draws from comprehensive reports coming out of Ontario and Halifax, among others. However, there are few studies on street checks with a Saskatchewan focus. To that end, the Commission worked with independent academic researchers (Thompson, Kaye, et al.) who produced a report on the subject: “Carding in Saskatoon: Dignity, Fundamental Freedoms and Equal Rights in Person Contact Interviews” (Thompson and Kaye Report).143

The Thompson and Kaye Report consists of four main topics:

- literature on street checks in Canada;

- an analysis of street check/contact interview data from 2009 to 2018 that was obtained through an Access to Information and Privacy application made to the Saskatoon Police Service;

- consideration of the law regarding detention and street checks in Canada; and

- community engaged research that gathered stories regarding the lived experiences of individuals who experience contact interviews in Saskatoon.144

It is important to note that the Thompson and Kaye Report was written based mainly on data and processes used prior to the implementation of the SPC contact interview policy. Terminology and processes may have changed since then.

A community research working group met from 2017-2019 with Elders, community-engaged researchers, racialized inner-city community representatives, and community-based organizations including STR8UP, Saskatoon Opportunity For Youth, OUTSaskatoon, AIDS Saskatoon, Station 20 West, CLASSIC, chokecherry studios, and the Elizabeth Fry Society of Saskatchewan.

Using a methodological design aimed at decolonial engagement with community, the working group held community conversations and developed and arts-based toolkit to explore the impacts of over-policing and under-protection in inner-city Saskatoon.145 Art-based community engaged research was used intentionally to harness storytelling, data collection, and artistic expression to empower participants to develop greater understanding of their individual rights, the community needs, and determine their vision of healthy community – specifically how they would like to be in relationship with the police.146

The Thompson and Kaye Report identified potential problems with the SPC policy, and outlines both individual and community harms that can be directly attributed to contact interviews and the data collection practices.

The Thompson and Kaye Report concludes that the current policy will not work to address the issues and concerns raised by the community and others.

While the Saskatchewan Human Rights Commission does not endorse this view, it is an important perspective.

Information Collection and Storage

The data collection system used by some police services in Saskatchewan consists of software from the company Versaterm. This software uses a standard digital form to collect information about what it calls street checks – which includes various types of police stops, including contact interviews, traffic stops, and checks performed by school liaison officers.147 Versaterm categorizes contact interviews as a subset of street checks.The data system also refers to contact interviews as “person contact interviews.” Here, again, terminology can be inaccurate.

The Versaterm street check digital form has three sections: general information, related persons, and reason for the stop. The persons section has 43 possible information fields including: sex, age, marital status, country of birth, citizenship, ethnicity, complexion, appearance, language, height, weight, accused status, employer, SIN, and gang name.148 The form lists ethnicity as a linkage factor to crime, in the same way that a criminal record or stolen car would be.149

When a new Versaterm form is opened, it auto-populates with information gathered about the person in other ways, and ethnicity is one of the data sets that auto-populates.150 The same Versaterm software used by police services is also integrated with other government ministries. It is not clear whether data is shared with government ministries or not.151 Section 3.1 of the SPC contact interview policy requires the forms to be deleted after five years, but is unclear whether information that may have auto-populated into other forms would also be removed or if it remains stored inside the Versaterm system.152

Police data management systems may not have an effective process for individuals to have their contact interview records (which are not criminal records) removed or nullified.153 The Commission heard from someone whose Indigenous son was stopped 18 years ago on his way to high school because police felt he met the vague description of a reported thief, and that information was still on his police file when he went to get a criminal record check in 2021.154 This is anecdotal, but raises important questions about data management practices.

In Ontario, Justice Tulloch encountered similar stories where people were refused employment opportunities because their name showed up as having a history of street checks (including when that person was not the person named in the police file, and merely shared the same name).155

Other jurisdictions, including Ontario, have legislation that prevents mental health checks and street checks data from being included on a criminal record check.156 Alberta has done preliminary research into the question of whether it should develop legislation protecting privacy during record checks.157

Community organization leaders told the Commission that court decisions such as Gladue and Ipeelee, which state that all aspects of the criminal justice system need to engage in working to reduce the numbers of Indigenous people in prison, would support measures to reduce the over-policing and over-criminalization of Indigenous communities as well.158 If there was accurate data to review, then you could see who is being stopped. However, at the moment, the only accurate data available to review in Saskatchewan is the prison population demographics. That population ranges between 70% to nearly 100% Indigenous at any given time.159 Without accurate data and/or oversight from the Saskatchewan Police Commission, it is difficult to be able to track compliance.160

While more accurate data could enable better examination for bias or discrimination, community organizations expressed concerns regarding the information that is collected and stored after a street check, and for what it is used.

In response to a demand for disaggregated data that better describes the lived experiences of racialized communities in Canada, Statistics Canada and the Canadian Association of Chiefs of Police proposed an initiative to collect data on the Indigenous and racialized identity of all victims and accused persons reported through the Uniform Crime Reporting Survey.161 This initiative is working towards national standards and guidelines for data collection and analysis.

Youth Feeback

In the Thompson and Kaye report, youth participants expressed feelings of confusion, threat, and nervousness when interacting with police, and were most concerned with the non- consensual nature of their interactions with police.162

During workshops with Saskatoon youths, a common sentiment was that they “don’t feel very safe and protected because the police aren’t there when you need them and there when you don’t.”163

Youths identified experiencing differential treatment based on growing up in lower socio- economic communities in Saskatoon, noting that “safety sounds like a privilege.”164 One youth described a street check as follows:

[I was] walking down 20th Street, I was walking – cop got out of the car, was on a mission, aggressive, threw me up against the wall, emptied my pockets and threw everything on the ground. That shit doesn’t make you feel good. Makes you feel like a bad person for nothing.165

Based on their lived experiences, youths generally expressed doubt about the stated purposes of street checks, noting that when officers say they are conducting an investigation, it seems like an excuse to stop someone. Others were “directly told by the police a prejudiced and discriminatory reason for the stop, such as ‘you look threatening’.”166

The Thompson and Kaye Report summarized studies that found various compromises in physical, social, and psychological health associated with experiences of racial profiling. Residing in a neighbourhood that is over-policed is considered a predictive factor for greater levels of anxiety and resentment caused by the anticipation of being stopped and questioned by the police.167

7. Issues to be Addressed

The Commission’s practice is to set out a pathway for constructive and collaborative stakeholder engagement that can respond to the issues raised in the report, rather than provide specific recommendations

Based on stakeholder consultations and our research, the issues to be addressed are broadly identified as:

1. Lack of knowledge among the public about contact interviews, and their rights more generally during police-citizen interactions.

Stakeholders suggest there is a need for better understanding of contact interviews and legal requirements associated with contact interview among the general public.

Comprehensive and publicly available policies and definitions may help explain the purpose, differences, and procedures of contact interviews, wellness checks,

investigative interviews, and detention. Plain language explanations should be available in the community.

2. Additional police training and education

Police-community relations could benefit from patrol officers engaging in meaningful and reflective training and accountability relating to anti-racism and trauma-informed practices.

Additional levels of contact interview training for officers could also help increase public confidence in these interactions. Appropriate training would include how to properly carry out contact interviews in a respectful manner and how to interact with people in a way that leaves community members with an understanding of why the interaction occurred.

3. Some uncertainty about the precise use and prevalence of contact interviews.

Despite significant improvement in the categorization and capture of information relating to contact interviews, the information obtained from police services’ annual submissions to the SPC suggest some inconsistencies across the province in the application of the SPC contact interview policy. The SPC has acknowledged this issue and indicated it will address it.

Also, it remains unclear how many police interactions with citizens begin as a contact interview – without any basis for criminal or statutory investigation – but end in an arrest. Improvements in reporting practices should be considered.

4. Lack of trust between certain communities and police services.

While some parts of the community support the contact interview policy, others remain critical. The Peelian policing model affirms that “the police are the public and the public are the police” to underscore the need for police to be, and see themselves, as a part of the community that they serve. It also requires that communities have an input into policing policies that are designed for them. Despite the current efforts of police services, there remains a need to build more responsive relationships with Indigenous and racialized communities to foster mutually beneficial police-community relations. It is in the interest of police, communities, police boards, civic leadership, and all stakeholders that policing reflects community interests and need.

Effective training about The Saskatchewan Human Rights Code and Code-compliant practices with all levels of police, including patrol officers, might work to address some of the concerns expressed by stakeholders, such as concerns about racial profiling.

5. Concerns about information collection and data retention.

Police services have varying policies on the collection of race data during contact interviews. Some police services are opposed to the collection of race data; others support it. Proponents of the collection of race data during contact interviews posit that it helps identify people who experience contact interviews, and to see whether or not race plays a role in police conducting contact interviews. Not all police services regularly audit and report contact interview data, and if they do, the metrics are not as transparent as community stakeholders need.

Safeguards related to data retention and sharing need to be implemented in order to respect privacy rights of individuals whose data is entered into the system.

Saskatchewan police services should continue to work with Statistics Canada to finalize protocols for the collection of Indigenous and racialized identity information.

CONCLUSION

Concerns about the use of street checks are common in all jurisdictions across Canada. Saskatchewan has been no exception with regard to its contact interview policy.

The SPC contact interview policy has provided clear direction to police services regarding how a contact interview can be lawfully conducted. Over the past few years, the reported statistics on contact interviews indicate broad compliance with the SPC policy.

It must be noted that the Public Complaints Commission’s annual report does not highlight contact interviews as an expressed matter of concern for complainants.

However, community stakeholders interviewed by the Commission indicated that they have yet to notice a change in police practice as a result of the contact interview policy. Moreover, they see a strained relationship between the public and police, in particular with community members who are Indigenous.

The SPC Policy acknowledges the importance of community relationships and trust:

“In conducting contact interviews members’ communication with the public must be informal, professional, fair, impartial, free of any element of physical or psychological intimidation, responsive to public concerns and of a nature that inspires public trust and confidence in and safeguards the legitimacy of policing.”

There is a need for further dialogue and discussions about the policy, contact interviews, and the community-police relationship.

Appendix 1

SPC Contact Interview Policy

(pages 101-104 of the Policy Manual for Saskatchewan Municipal Services) OC INVESTIGATION

OC 150 CONTACT INTERVIEWS WITH THE PUBLIC

NEW: Revision # 13, May 17, 2018

1.0 STATEMENT OF PRINCIPLES:

Community safety is most effectively achieved and enhanced when police and communities

work together as partners to pursue common objectives. The public expect members of a police service to engage with the people of the communities they provide service to, to

become familiar with the community and its residents and to continuously communicate with them. For that reason, police services throughout Saskatchewan and the Saskatchewan Police Commission remain committed to Community Policing as their approach to serving our communities effectively.

In order to maintain public confidence in policing, members of a police service must ensure that when their contacts with residents of the community are more than normal social interaction, they are conducted in a manner that is diligent in its respect for the law and the fundamental freedoms and human rights of the public.

2.0 DEFINITION – CONTACT INTERVIEW:

For the purposes of this policy, “contact interview” means a contact with the public initiated by

a member of a police service with the intention of gathering information not related to a specific known incident or offence. The information being sought must be more than general information common to the community. It does not include, nor does this policy apply to:

- normal social interaction or general conversation with the public where the member has no cause for concern in regard to the purpose, behaviour, demeanor or welfare of the person they are speaking to;

- contact initiated by a member of a police service working in an undercover capacity;

- visual observations made by a member of a police service where no actual contact with the public is initiated;

- circumstances in which investigative detention is authorized by law; or

- contact initiated pursuant to specific statutory authority such as checks authorized under The Traffic Safety Act or other provincial or federal statutes.

Where contact is initiated pursuant to specific statutory authority, this policy applies to the extent that the information requested by a member of a police service exceeds that statutory authority and such portion of the contact constitutes a “contact interview”.

Contact interviews may only be conducted in a manner that respects and protects the rights of the public under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, the Canadian Bill of Rights, The Saskatchewan Human Rights Code, the Canadian Human Rights Act, and similar federal and provincial human rights legislation, and may not be conducted by members of a police service on a random or arbitrary basis.

Contact interviews are appropriately conducted by members only where the subject’s behaviour or the circumstances of the contact cause the member to have a concern as to the subject’s purpose or for the subject’s safety. Circumstances which should be considered and which may give rise to a concern would include:

- there is no apparent reason for the subject’s presence in a particular area, such as being present in a commercial or industrial area late at night when everything in the area is closed;

- the subject’s actions, behaviour or demeanor raise a concern as to his/her purpose or for his/her safety; or

- the subject appears to be lost, confused, frightened or in need of

In the absence of actions, behaviour, demeanor or circumstances giving cause for concern as set out above, contact interviews may not be conducted based solely on the subject’s:

- location in an area known to experience high levels of criminal activity and / or victimization;

- actual or perceived race, ethnicity or national origin;

- colour;

- religion;

- age;