Initiative Update:

The Saskatchewan Human Rights Commission recently held four information sessions pertaining to its Equitable Education for Students with Reading Disabilities initiative:

- Parents Information Session (Feb. 27)

- Stakeholder Information Session (Feb. 28)

- Stakeholder Information Session (Feb. 29)

- Public Information Session (Mar. 8)

The featured speakers at these events – Alicia Smith (Dyslexia Canada), Dr. Andrea Fraser (Mount Saint Vincent University), Maria Soonias Ali (SHRC), and Kirsten Downey (parent) – discussed reading disabilities, curriculum, instruction, pedagogy, parental concerns, as well as potential solutions and improvements to the challenges raised in the Equitable Education for Students with Reading Disabilities report.

To view the Public Information Session click HERE.

In June 2020, the Saskatchewan Human Rights Commission received a group complaint on behalf of 29 families, all with children who have been professionally diagnosed with dyslexia. The families alleged that eight school divisions discriminated against their children on the basis of disability (dyslexia and other disabilities) and that the school divisions violated their children’s right to fair and equitable access to education. The families preferred a systemic investigation into the identification, treatment, and accommodation of students with reading disabilities in Saskatchewan. Working collaboratively with numerous stakeholders, the Commission conducted research and surveys to develop a report using a systemic investigation and advocacy approach. The report, Equitable Education for Students with Reading Disabilities: A Systemic Investigation Report, provides a summary of the Commission’s findings. The Commission considers this work to be the beginning of a process of improvement. Further collective efforts are required to achieve the goal of eliminating systemic discrimination. For more information about this initiative, contact [email protected]

Contents

1. Chief Commissioner’s Message

Reading is a fundamental skill. Many would argue it is the most important skill, not just for academic pursuits, but for nearly all aspects of life. Education systems are responsible for ensuring that every student learns to read. All students, including those with disabilities, have the right to equitable access to education.

Being able to read is a factor in a person’s quality of life, regular social interactions, access to employment, and income possibilities. Unfortunately, many students with reading disabilities are not learning this foundational skill, leading to immense challenges for both students and their families.

This report provides a thematic and objective view of survey responses, a legal summary, and a literature review on reading disabilities. It is not an exhaustive analysis of inequity experienced by students with reading disabilities or a full analysis of the practices and policies within the Saskatchewan education system(s). Rather, the intent is to gather and synthesize the concerns raised by students, parents, caregivers, teachers, and other professionals.

It takes trust, courage, time, and energy for people to share their experiences. The Saskatchewan Human Rights Commission is grateful to everyone who took the time to participate in this initiative through interviews, submissions, surveys and consultation. These contributions have added greatly to this report and in bringing these concerns to light.

The Commission considers this report to be the beginning of a process of collaborative improvement. The Commission is committed to working with stakeholder groups, through multiparty discussion, to respond to, address, and remove inequity and systemic barriers experienced by students with reading disabilities. Such collective efforts are required to achieve the goal of eliminating individual and systemic inequity.

Barry Wilcox, K.C.

Interim Chief Commissioner

Saskatchewan Human Rights Commission

2. Introduction

The Saskatchewan Human Rights Commission

The Saskatchewan Human Rights Commission (the “Commission”) is mandated to forward the principle that every person is free and equal in dignity and rights without regard to religion, creed, marital status, family status, sex, gender identity, sexual orientation, disability, age, colour, ancestry, nationality, place of origin, race or perceived race, or receipt of public assistance. The Saskatchewan Human Rights Code, 2018 (the “Code”) prohibits discrimination based on these personal characteristics. Discrimination in specific areas of social life, including in education and employment, which contravenes the Code, is illegal. The Code requires the Commission to respond to individual as well as systemic complaints of discrimination.

What is Discrimination?

Discrimination is any unfair action, policy, or practice that puts a person or group at a disadvantage by treating them differently from others, or by applying the same rule to everyone, resulting in a person or group being unjustly denied opportunities or receiving fewer benefits in what are often called the social areas of life (e.g., education, employment, housing).

Discrimination can flow from prejudice, negative stereotypes, or a failure to consider the needs of others. Sometimes discrimination is deliberate and direct – such as the use of racial slurs or refusals to employ someone because of their race – but it can also be indirect or unintentional.

The Systemic Approach

Allegations of discrimination can be addressed through the Commission’s individual complaint process. The Commission also has a legislated mandate to address systemic discrimination through Section 24(h) of The Saskatchewan Human Rights Code, 2018. The Commission uses systemic approaches, including multiparty dialogue, to address discrimination and inequity, including differential treatment, policies, rules, or actions that unfairly disadvantage an identifiable group.

The Commission’s systemic investigations examine systems to uncover subtle or hidden processes (policies, procedures, and practices – both official and informal) that may be contributing to unfair disparities and discrimination. Once problematic processes are identified, they can be reviewed and revised as required to eliminate and remedy inequity and other barriers. Such an examination also highlights any existing positive processes and notes past and current successes.

The Reading Disabilities Systemic Complaint

In June 2020, the Saskatchewan Human Rights Commission received a group complaint on behalf of 29 families, all with children who have been professionally diagnosed with dyslexia. The families alleged that eight school divisions discriminated against their children on the basis of disability (dyslexia and other disabilities) and that the school divisions violated their children’s right to fair and equitable access to education. The families expressed their desire for a systemic investigation into the identification, treatment, and accommodation of students with reading disabilities in Saskatchewan.

Given the number of parents supporting the complaint, the Commission determined a systemic approach was more efficient and appropriate than pursuing each complaint individually. In this way, the Commission could take a broader view of the issues and present better systemic resolutions.

The scope of the systemic initiative includes the review of the parent submissions, conducting stakeholder interviews and meetings, the preparation of a legal summary, and capturing the comment, feedback, and input of individuals with reading disabilities, their families, and advocates, as well as educators and other professionals. The systemic initiative, and this summary report, are intended to be stakeholder engagement tools to help address the concerns of those affected by reading disabilities in Saskatchewan schools.

Reading Disabilities as a Systemic Human Rights Issue

Reading is an important skill for nearly all areas of life. Addressing systemic barriers that exist for students learning to read has the potential to improve the lives of many individuals and the communities in which they live. Students with word-reading disabilities such as dyslexia and other learning disabilities, students from lower-income backgrounds, racialized students, and Indigenous students are all at a higher risk of falling behind their peers when it comes to early reading.[1]

The issues raised by parents in Saskatchewan are not unique to this province. The Ontario Human Rights Commission (the “OHRC”) conducted an inquiry which culminated in the publication of a substantive report titled “Right to Read: Public inquiry into human rights issues affecting students with reading disabilities.”[2] The report was released publicly in 2022.

There is congruence between the issues identified in the OHRC report, the concerns raised by parents here in Saskatchewan, and the Commission’s findings.

The Reading Disabilities Systemic Initiative

From the start, the parent complaints the Commission received suggested the initial themes that helped determine the scope of the systemic initiative process. To further refine the process, the Commission consulted with individuals and stakeholder groups, including educators, professionals, and community-based organizations. In addition, the Commission met with the Ministry of Education and spokespersons for school systems.

Although the COVID-19 pandemic and related restrictions curtailed meetings between the Commission and in-person audiences, the Commission sought out and received public participation through two online surveys. One survey was designed for students/families who have lived experience with system navigation, accommodation, and other aspects of learning to read in the context of reading disabilities.

The second survey was designed for teachers, school administrators, psychologists, speech-language pathologists, occupational therapists, and other professionals who work with students who have, or may have, learning disabilities. Survey information was distributed with the assistance of the Ministry of Education, the Saskatchewan School Boards Association, and other organizations.

Stakeholders

The Commission is committed to working with stakeholders to ensure equitable access to education for students with reading disabilities. The array of involved individuals and organizations include:

- Students, their families, and caregivers who are currently navigating the education system (and will continue to navigate it in the future) are major stakeholders in the outcome of this report.

- The Saskatchewan Ministry of Education is ultimately responsible for education in the province. It provides funding to the various school divisions, sets the curriculum, and can set additional provincial standards.

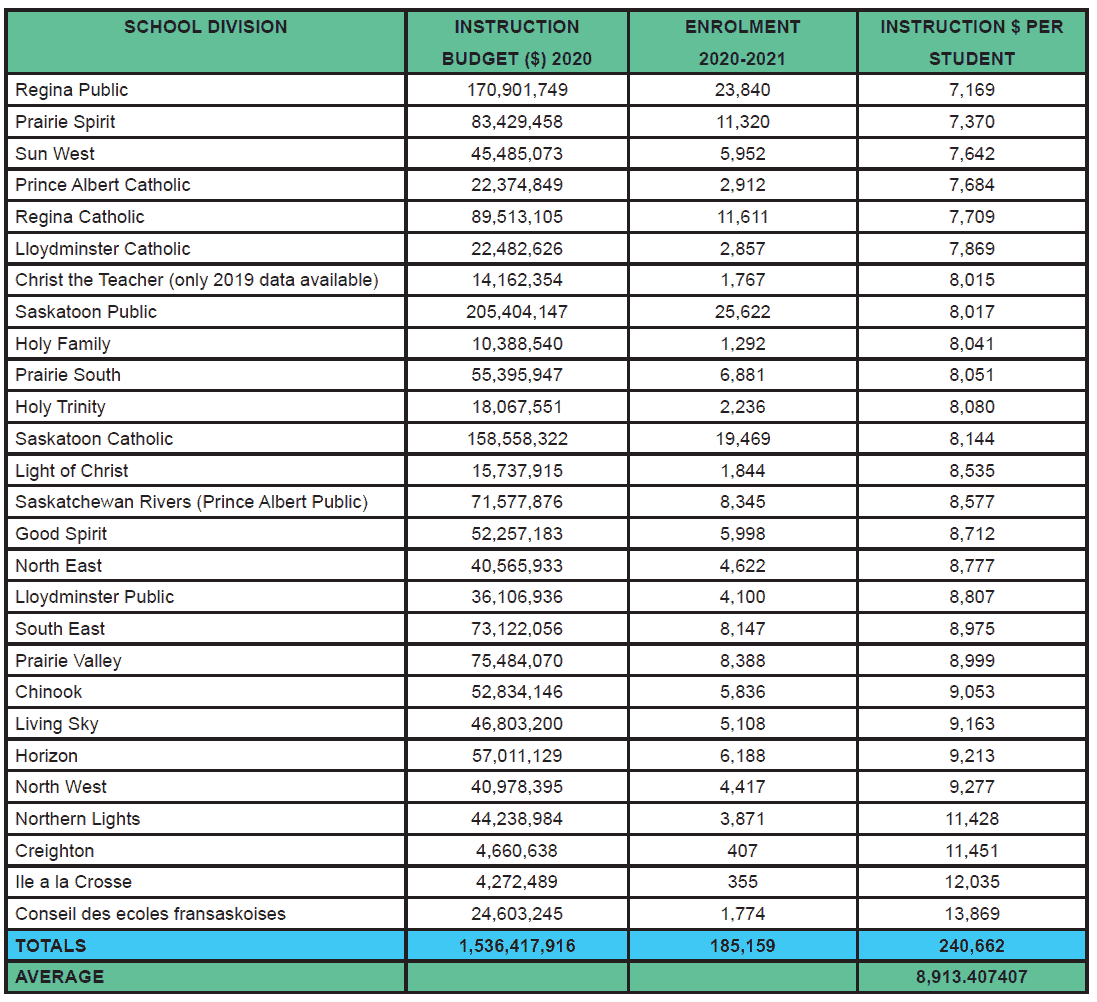

- The Saskatchewan School Boards Association represents all 27 school boards in Saskatchewan. Each division has a great deal of autonomy to spend the funds provided by the Ministry to deliver education services. The Saskatchewan School Boards Association advocates for divisions across the province, which include 18 public school divisions, eight separate Roman Catholic school divisions, and one Conseil Scolaire Fransaskois.

- K-12 educators and professionals, including principals, teachers, special education teachers, early childhood educators, educational assistants, literacy specialists, and educational psychologists have specific roles and collaborative opportunities to engage with and support students with reading disabilities.

- Faculties of education play a key role in preparing teachers to teach students early reading skills. The University of Saskatchewan and University of Regina offer teacher education in the province through a variety of different programs, including ITEP, SUNTEP, as well as other distance and online learning programs. Teacher training is recognized as a primary factor in the reading skills acquisition of students with reading difficulties and disabilities.

- Education sector partners such as the Learning Disability Association of Saskatchewan, College of Psychologists, College of Physicians and Surgeons, Dyslexia Canada, speech-language pathologists, audiologists, occupational therapists have specific experience in diagnosing and accommodating students with learning and reading disabilities.

- At a national level, advocacy organizations such as Dyslexia Canada and agencies such as the Ontario Human Rights Commission add to the informed stakeholder base by identifying how learning to read is a human rights issue, and not merely a budgetary or philosophical matter.

It is the hope of the Commission to work collaboratively with each of the above-mentioned stakeholders upon release of this report. The Commission intends to provide support and ensure the work yet to come remains focused on the right to education that children in Saskatchewan inherently have and more specifically the rights of children with reading disabilities.

3. Literature Review

Importance of Early Reading

Learning to read is a complex process. For most children, learning to read does not come easily or naturally from exposure to language or reading. Reading is a skill that must be taught.[3] Written language is a code that represents spoken language and students must learn to “crack the code.”

Literacy goes beyond the ability to read and write proficiently. It includes the ability to access, receive, analyze, and communicate information in a variety of formats, and to interact with different forms of communication and technologies.[4] The ability to read is a critical skill necessary to navigate life in school and beyond. In the early years of schooling, students learn to read, after which most are expected to read to learn.

Difficulties with reading early on inevitably affect the quality of education and type of educational experiences someone can have; consequently, reading difficulties affect a person’s desire or ability to stay in school to graduation and pursue post-secondary education. They also negatively affect future employment prospects, earning potential, a person’s mental health, and the lives of their immediate family and friends. Overall, quality and direction in life is directly affected by an individual’s ability to read.

Learning to read in the early years enables students to learn a skill they carry with them throughout their lives. The goal of reading is to understand and make meaning from what is read. Good reading comprehension requires being able to read words accurately and quickly. It also requires good oral language comprehension, including strong vocabulary and background knowledge.[5] For people who have successfully acquired this skill, it can be easy to overlook how challenging many areas of life can be for those who have a reading disability.

Health outcomes for people with lower levels of education and lower literacy skills are much poorer compared to people with high levels of literacy. The development of reading proficiency in childhood is also a public health issue; literacy is a determinant of health. The repercussions of low literacy move into the areas of social, vocational, and economic success of which those with lower rates of literacy also have much poorer outcomes than those with high(er) rates of literacy. Consequently, very few areas of life are comparatively unaffected by literacy rates.[6]

When it comes to reading disabilities the passage of time is one of the greatest enemies. The sooner remedial action can be taken the better the result. In this case, an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. Not addressing the issues at a young age will add to the difficulty and expense of assistance later in life.

Defining Learning and Reading Disabilities

Learning disabilities may present in different forms: reading, writing language, oral language, and mathematics. When a child’s ability to acquire or apply reading skills, such as phonetic knowledge, word recognition, comprehension, and decoding is chronically affected, that is defined as a reading disability.

The prevalence of dyslexia for example, is estimated to be around 20% of the population and represents 80–90% of all those with learning disabilities. It is also the most common of all neuro-cognitive disorders.[7]

However, a lack of adequate surveying, reporting and varying definitions and measurements mean that the percentage of the Canadian population with a reading disability, namely dyslexia, could be higher than current, formal numbers estimate.[8] Statistics Canada’s surveying shows that an estimated 3.2% of Canadian children have a learning disability.[9] However, changes are being made to their surveying process to gain a more accurate number.

Reading disabilities have varying levels of severity, ranging from mild, moderate, and severe. Individualized intervention, support, and accommodation are key factors in remediation and success. For example, a person with “double deficit” dyslexia exhibits impairments in both phonological processing and rapid symbolic naming skills. This is the most severe sub-type of dyslexia and the most difficult to remediate.

Effective instruction must include intensive phonological awareness training alongside explicit and systematic instruction in decoding and spelling.[10] An individual with any form of dyslexia, students that are diagnosed or are suspected to have attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), or students that generally struggle with reading would benefit from adjustments to duration, pacing, and the behavioural supports that some reading pedagogies may highlight more than others.

The current Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) criteria for diagnosing a learning “disorder” requires that:

- The student experiences difficulties in reading, writing or math skills, which have persisted for at least six months even though the student has received interventions that target the difficulties;

- The difficulties result in the affected academic skill(s) being substantially and quantifiable below those expected for the student’s age. This is determined though standardized achievement tests and clinical assessment;

- The learning difficulty started during school-age years (or even in preschool), although it may not become fully evident until young adulthood in some people.

It is important to note that a diagnosis of dyslexia and various other reading disabilities, is not an indication of intelligence. On the contrary, many people who live with dyslexia also have a variety of strengths, such as:[11]

- Brilliant spatial reasoning,

- Abstract thinking skills,

- Critical thinking skills,

- High levels of creativity and imagination,

- Excellent problem-solving skills, and

- High levels of empathy.

Use of the Term Dyslexia

The terms dyslexia, reading disability, and reading disorder are often used interchangeably, but they are not synonymous. Dyslexia is a specific disorder that affects a person’s ability to read. The core challenges for individuals with dyslexia include phoneme awareness, rapid automatic naming of symbols, phonic decoding, spelling, written expression, and automatic word reading (reading words seemingly “by sight”).[12]

Dyslexia is considered the most common type of reading disorder. The Diagnostic or Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) recognizes dyslexia as an appropriate term for referring to a pattern of learning difficulties characterized by problems with accurate or fluent word recognition, poor decoding, and poor spelling abilities.

The use of the term dyslexia has been abandoned by some; others consider the term controversial.[13] The Ministry of Education and many schools in Saskatchewan have moved away from using the term dyslexia, particularly as the education system has shifted away from a medical model to a needs-based approach of providing additional supports to students.

However, advocates and parents alike emphasize that dyslexia is well researched, understood, and recognized by the public. Using the term dyslexia to describe specific impairments, rather than simply using the umbrella term “reading disability,” may also be advantageous in that it is more specific and can help to clarify what intervention is required. After a diagnosis, an individual and their family can research and access the many resources available. They can also focus on what the diagnosis means, and how to move forward with what the child needs in order to learn.

Barriers to Learning to Read and Impacts on Students

If not addressed early, barriers to learning to read can create frustration with, and a dislike for, reading as well as school in general. Difficulty or inability to read affects confidence in a child’s learning abilities, academic performance, and overall mental health. From an early age, students can recognize what comes easily to their peers is difficult for them. Unfortunately, students with reading disabilities often underachieve academically. They are more likely to drop out of school, less likely to go on to post-secondary education, and tend to take longer to finish programs they enroll in.[14]

The Commission’s own survey results[15] show that students experiencing reading disabilities may engage in protective defense mechanisms, such as avoidance. This can negatively affect a student’s relationships and mental health. Some of the respondents from the parent survey stated that students who are told they don’t work hard or don’t apply themselves are often already working much harder than others to maintain their current level of reading. It was also shared that many of the respondents from the parents surveyed saw that their children also began to believe the negative things they heard about themselves, especially if it came from someone in authority, such as an educator. The result can be harmful to students who internalize difficulties with reading as their fault, or that they are less intelligent than their peers, when in fact they may just learn differently.

Removing barriers for students with reading disabilities may also benefit students with other disabilities such as intellectual disabilities, developmental disabilities, hearing disabilities, vision disabilities, autism spectrum disorder (ASD), and ADHD who often struggle with reading for many of the same reasons as students with reading disabilities.

Barriers to Learning to Read and Lifelong Impact

While education and employment are obvious and major areas of an individual’s life that would be impacted by a reading disability, particularly if that individual has not benefited from individual and adequate intervention or accommodation, all areas of life from reading a restaurant menu to texting and functioning online could be greatly impacted. Adverse effects can continue over the person’s lifetime, leading to increased risk of under employment, relying on social assistance, poverty, homelessness, and criminalization.[16]

Research also shows that many people with reading disabilities tend to have more psychological problems, including depression, anxiety, and substance-use disorders than people who do not. [17]

Broader Social Impacts

The broader impacts of low literacy on society have been well researched and documented. In 2007, the Roeher Institute prepared a report for the Learning Disabilities Association of Canada which estimated the direct and indirect costs that result for and from a person in Canada living with a learning disability.[18]

Costs arising from hospital and medical services, medications, miscellaneous health-related expenses, education services, criminal justice services, income transfers through social assistance programs, services provided by community agencies to assist with every day activities because of disability, reduced earnings of people with learning disabilities, reduced household incomes (forgone income related to taking care of persons with learning disabilities), equate to an estimated cost of $1.982 million per person with a learning disability from birth to retirement.

It is important to note that 61.4% of that cost falls on the individual and their family, with the remaining balance being covered by public programs (38.5%), and 0.1% can be attributed to private sector insurers for medication costs. At that rate, if an estimated prevalence rate of 5% of the Canadian population has a learning disability, the overall cost of all unremedied learning disabilities add up to about $707 billion from birth to retirement in year 2000 dollars (approximately $1.12 trillion in 2023 dollars).

Statistics like these demonstrate the large repercussions, either positively or negatively, that even small variations in percentages of the population can have. The value of being able to read is substantial to society as a whole. So much so that it is estimated that even a 1% increase in graduation rates could save the Canadian economy $7.7 billion per year (figures used were estimated in 2008). This equates to savings in the areas of health, social assistance, crime, labour, and employment.[19]

It would also serve to address the mental, physical, and emotional burden on those with a learning disability and those who function as their direct supports and advocates.

Research done by the Canadian Association of Chiefs of Police (CACP) has identified the benefit of improving literacy as a tool to combat crime.[20] The CACP report also recognizes the intersectionality between literacy and factors such as poverty, racism, being an immigrant, being Indigenous, and having a disability (including learning disabilities).[21] People with childhood learning disabilities are over-represented among homeless youth and adults and are also disproportionately involved with the criminal justice system and in correctional facilities.[22]

At the time the CACP report was written, an estimated 2.6 million Canadians that suffer from chronic low-income employment or unemployment require literacy support to improve their quality of life and raise themselves out of poverty and persistent unemployment.[23] Therefore, a change to our education systems may have major, long-term benefits not only to those directly affected by learning disabilities, but for the quality of life of millions of Canadians.

Research into the life-long effects of not being able to read, societal costs, and options that exist to support people with reading disabilities, demonstrates the need to exercise a variety of methods to support those living with this disability.

A primary preventative measure is equitable and quality education and enforcing changes that will benefit not only those with reading disabilities, but also their peers,teachers, educators, and specialists alike.

Ableism

Ableism is a belief system, similar to racism, sexism, or ageism, that sees persons with disabilities as less capable or worthy of respect and consideration than others.

Whether intentional or unintentional, the lack of understanding related to reading disabilities has been seen to perpetuate the effects and damage of ableism. Lowered expectations for certain learners – including students with disabilities – have resulted in systemic failures in the education system.[24]

Lowered expectations for students who have reading disabilities and struggle with reading are a form of ableism. For students with dyslexia and reading difficulties, it is simply untrue and unacceptable to believe they will not read as well or meet grade level standards, similar to their peers, when they are provided timely and appropriate instruction and intervention.

There is an intersection between students with dyslexia and other disabilities, students from lower-income backgrounds, racialized students, and Indigenous students, that could also equate to subtle or overt forms discrimination based on race or class. This can create even greater barriers and challenges for these students to access and receive the supports they deserve and require, and their ability to feel they can advocate for themselves.

Public education systems have a responsibility to improve educational outcomes, which can form an equitable tool to find success in life. Modern definitions of literacy include the essential elements of being able to read and write proficiently, as well as the ability to access, take in, and analyze information. The ability to read can be a gateway to all other knowledge.

Provincial Literacy Goals, Activities, and Outcomes

The Ministry of Education’s 2019-2020 Annual Report outlined specific targets for students in Saskatchewan. These targets included having 80% of students at or above grade level in reading, writing, and math by June 2020. While this number may appear high, this means that 20% of students are not expected to be meeting the desired standards. This equates to one in every five students (or approximately 36,000 students) in Saskatchewan that are not expected to meet desired standards.

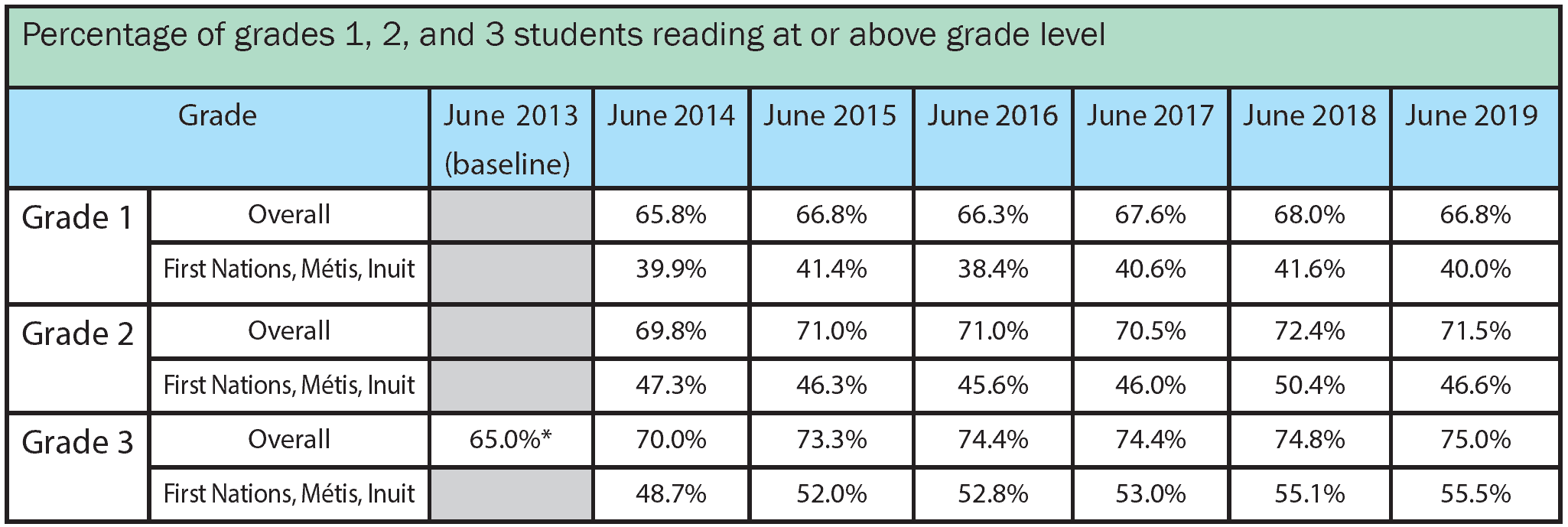

The 2019-2020 Annual Report also details the reading achievement of self-declaring First Nations, Métis and Inuit students, and the general population, for students in Grades 1- 3 between 2013 and 2019.

The table below indicates the number of students reading at or above grade level remains below the 2020 target according to provincially developed benchmarks.[25]

Performance Measure Results

Reading, Writing, and Math Achievement [26]

The Saskatoon Public School Foundation’s 2020-2021 Annual Report aligns with the provincial data, stating that, each year 28% of Grade 3 students in Saskatoon schools do not meet grade level reading standards. This appears to be an ongoing statistic as this finding was previously cited in their 2017-2018 Annual Report.[27] This data suggests that a portion of the student population may go through their school years struggling to learn due to reading challenges. As described earlier, studies report that students facing such unremedied, year-after-year challenges are more likely to leave school early.

In its 2020-2021 Annual Report,[28] the Ministry of Education listed literacy as one of its six goals, calling literacy a community priority that “contributes to residents’ lifelong learning and participation in the economy.”[29] Key actions the Ministry has taken to make progress in this area include:

- Renewing the family literacy program,

- Supporting family literacy hubs and improving their services for Indigenous families,

- Supporting library programming for newcomers and people with print disabilities,

- Exploring the demand for more summer literacy programs,

- Focusing on accessible library services, and

- Distributing literacy kits during the COVID-19 pandemic.[30]

These goals do not address the need for a systematic and scientific review of currently practiced reading methods and classroom instruction, their effectiveness, or direction for improvement. They also do not address the need for a provincial curriculum review or update, which would ideally include greater detail and explicit instruction for teachers and educators to use as measurements of achievement for students.

The 2020-2021 Annual Report also outlines ways to improve literacy in the province. Potential methods include: improving access to books, promoting reading, working in connection with the province’s libraries, summer reading programs, and promoting the value of reading in the community.

Other literacy improving actions included:

- Eight hundred students participated in 20 summer literacy camps hosted in northern Saskatchewan,

- The use of evidence-based approaches being emphasized, and supports for school divisions to support these students,

- Supporting All Learners modules developed with the goal of supporting learners in an inclusive environment, and

- Eight school divisions participated in providing literacy programs to 1032 students in 2020. The average daily reading time per participant was unavailable for 2020 due to the pandemic.

When reached for further detail on attendance and programming, a Ministry representative clarified that each of the eight school divisions (29 communities, mainly in the central and northern areas of Saskatchewan) make the choice as to which students will attend a literacy camp.[31] When asked how many spaces are reserved for children with severe difficulties reading or specific reading disabilities, it was indicated that would be arranged entirely by the individual school divisions.[32]

Literacy camps are a valuable tool to assist struggling readers and children with reading disabilities. However, they should not be seen as a replacement for quality instruction in the classroom and should strive to support students that fall into both Tier 2 and Tier 3 categories.

Approaches to Reading Instruction

Balanced literacy

Balanced literacy has a focus on the “balance between teaching based on the use of whole texts and teaching about the alphabetic code and other linguistic features. With this approach, the importance of comprehending the meaning of written language is balanced with the acquisition of a range of skills and knowledge. Lessons make explicit links between phonics teaching and other linguistic aspects using whole texts, which are often a combination of real books and reading scheme books with controlled vocabularies.”[33] Teachers “gradually release responsibility” by modelling, sharing, guiding, and then allowing students to read texts independently.[34] To accomplish this, teachers may use a variety of approaches to instruction including word-solving strategies, word studies, interactive writing, and phonics lessons (although the systematic and sequential aspect of this differs from structured literacy). It may often employ the “three-cuing system”[35] which encourages students to figure out words using cues or clues from the context and their prior knowledge.

One of the most acknowledged methods of using and teaching balanced literacy is that of Fountas and Pinnell, which has a vast following within the educational sphere of North America and is regularly used within Saskatchewan.

Saskatchewan Reads, a companion document to the Saskatchewan English Language Arts Curriculum Grades 1, 2, and 3, emphasizes the use of balanced literacy. It showcases what it has identified as “promising practices that have proven successful in school divisions and First Nations communities within Saskatchewan.” Some examples include, Picture Word Inductive Model (PWIM), Reader’s Workshop, Balanced Literacy, Scaffolded/Guided Reading, Levelled Literacy Intervention and Running Records. The documents say the motivation to create Saskatchewan Reads came from the need to improve student reading in the province.[36]

Structured Literacy

A structured literacy approach involves systematic, cumulative, and explicit instruction in the relationship between sounds in speech and the written word, phonics, the use of decodable texts, and varied age and skill-level appropriate literature. Structured literacy is the method of teaching reading with direct and systemic instruction in foundational reading that also benefits a student’s writing and speaking skills.[37] It does not focus on discovery and inquiry-based learning.

In 2000, the US National Reading Panel released an influential report entitled: Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction. This report outlined five important aspects of teaching children to read. These aspects have been adapted to be more commonly known as the Five Big Ideas in Beginning Reading or The Five Pillars of Reading Instruction.[38] They are as follows:

- Explicit instruction in phonemic awareness.

- Explicit and systematic phonics.

- Teaching methods to improve fluency.

- Teaching vocabulary.

- Teaching strategies for reading comprehension.

The Canadian Language and Literacy Research Network Report, Foundations for Literacy: An Evidence-based Toolkit for the Effective Reading and Writing Teacher, 2008, noted that structured, systematic, and explicit teaching, with structured practice and immediate, corrective feedback is important in teaching all students, and is especially important in teaching students with dyslexia.[39]

Structured literacy is the instructional approach both scientific researchers and advocates for students with dyslexia say is the most effective way to teach early reading.

Perspectives on Instructional methodologies

Many parents who contacted the Commission, either with individual concerns or the group complainants, shared their frustration with current methodologies used when teaching reading to children with reading disabilities. Many told us that the balanced literacy approach to teaching reading, which is applied by the Ministry and most school boards in Saskatchewan, is problematic for children with reading disabilities. The Commission’s own research and consultation from a vast array of sources has shown the science and research behind the structured literacy approach to be superior to the balanced literacy approach and has been proven to serve a wider audience of learners, including those with dyslexia.

The Ministry of Education has previously maintained that balanced literacy covers all components of reading.

While balanced literacy appears to be the primary focus on learning throughout the province, with some exceptions and variations, the view of the majority of those surveyed by the Commission see benefit in adopting a change in method in order to better suit more students, including those struggling with reading.

“Children – particularly those who are not strong readers – are routinely subjected to teaching practices that have not been shown to be effective for children like themselves. These include teaching students to rely on context, pictures, and guesswork to decipher new words, instead of decoding the sound-symbol relationships.”[40]

Internationally, England, Australia and many US States have also moved away from using balanced literacy as their primary pedagogy. Some Canadian jurisdictions have moved away from this approach in recent years, including Ontario.

An excerpt of a press release from the First Nations School Board in the Yukon, released on February 8, 2023, stated:

“Since the FNSB was established in February 2022, they have been working on researching, developing, and implementing a Literacy Plan that addresses the urgent problem of low literacy rates among Yukon students, as described in both the 2009 and 2019 Auditor General’s Report on Education … The science of reading, an extensive and proven body of research, shows that students best learn to read following very explicit methods, specifically, a structured literacy approach. This research also points to the problems with balanced literacy approaches, such as Reading Recovery and Fountas and Pinnell, both of which have been used across Yukon public schools for over a decade.”[41]

Intersectionality

Students in Saskatchewan schools come from a wide variety of backgrounds. As the issues around learning to read are explored, it is important to note that not all students are equally situated. People are more than any single personal characteristic they possess (e.g., race). Every person’s identity is influenced by the culmination – or intersection – of many personal characteristics and identities (e.g., age, gender, disability). This is the doctrine of “intersectionality.”[42] In turn, an individual or group may experience discrimination based on the intersection of prohibited grounds such as sex (“sexism”), disability (“ableism”), or age (“ageism”).

Intersectionality has several practical effects on learning for Saskatchewan students. The challenges faced by students with reading disabilities can often be amplified for Indigenous students, multilingual students, students from lower income homes, racialized students, and students with more than one disability. Onus is placed on parents to work with children at home and this may be more difficult for some due to an intergenerational lack of literacy, reluctance towards the traditional school system, or a lack of understanding about how to navigate the system.

Some parents themselves may have learning disabilities that were never identified or supported. Socioeconomic standing and poverty may create even larger barriers to accessing assessments, assistive technology, or other types of accommodations. These barriers are amplified when students live in rural and/or remote communities.[43]

Families need to feel understood and supported when dealing with the confusion of managing a child’s educational needs and navigating a confusing education system in order to see their needs met. For a variety of reasons, not every child has the required support and advocacy to help them through this process. While familial support is a major benefit for a student with a reading disability, parents expect the Saskatchewan education system to function in a way that doesn’t leave any child behind.

Students with other disabilities may also struggle to learn to read when approaches used in the classroom prove ineffective. Because of marginalization and structural inequality, racialized students, Indigenous students, Métis students, multilingual students, and students from low-income backgrounds are at increased risk for reading difficulties.[44] While there may be a very small percentage of students who ultimately may never learn to read, it is important to guard against this as a guiding assumption. Most students with reading disabilities can learn to read.

As mentioned earlier in this report, assuming that students with disabilities will never learn to read or read well is a form of ableism. Such an assumption can be used to justify maintaining systemic barriers instead of making necessary changes that will help all students learn to read.[45] It is important to note that having low expectations for students from Code-protected groups is a form of discrimination. It is also important to note that there is limited data in Saskatchewan connecting reading achievement with factors such as race, place of origin, gender, socioeconomic status, or other identities.

Indigenous Students

Bridging the gap and working towards greater equity

“At present, the goals of Indigenous literacy policy do not match with the linguistic, cultural and social contexts that young learners inhabit, particularly those living in remote communities, nor do they encourage or make space for such perspectives and partnerships to form. Rather, current settings endorse proscriptive programs of literacy learning, such as DI [Direct Instruction], which empty out the realities of context. While there are a multitude of suggestions that can be made for bridging the divide between education policy making and Indigenous literacy learning, the key is to be found through doing policy ‘with’ rather than ‘to’ communities.”[46]

For a variety of historical and current reasons, Indigenous students require and deserve recognition and support. Canadian history is marred by injustice, racism, bias, and mistrust between Indigenous peoples and the settler communities. Intergenerational trauma, residential schools, the 60’s Scoop, the ongoing pain of missing and murdered women and girls, disproportionate representation within the child-welfare system, as well as in the justice system, along with the ongoing systemic inequities that continue to be perpetuated create significant challenges in all areas of life for Indigenous peoples in Canada. Education is no exception. For some Indigenous learners, a reading disability may subject them to another layer of discrimination. This is the concept of intersectionality.

Indigenous students in Saskatchewan have lower graduation rates and lower reading levels compared to their non-Indigenous peers. In 2016, research showed that 29% of Indigenous people in Saskatchewan had no certificate, diploma, or degree, which was higher than the overall Indigenous population within Canada (26%), and non-Indigenous people in Saskatchewan (10%).[47]

Furthermore, the 2023 Provincial Auditor of Saskatchewan’s Report (Vol. 1), cited that in the Regina Public School Division, only 37% of Indigenous students were reading at or above Grade 3 reading levels in 2020-2021 as compared to the entirety of the Grade 3 population at 58%.[48] Data collection, statistics, and research such as this have been used to inform the Auditor’s conclusion[49] to recommend the Ministry of Education:

- Expand measures and targets it sets for Indigenous student academic achievement beyond graduation rates.

- Require enhanced reporting from school divisions on Indigenous student success.

- Determine actions to address root causes of underperforming measures related to Indigenous student success.

Various efforts are ongoing to assist with this educational gap, but there is much more that can be done. Focusing on culturally relevant and implemented universal screening, increasing access and funding for assessments, increasing data and reporting requirements, and creating ongoing supports and intervention for all students within our province could lead to a more equitable outcome for Indigenous students and their families.

Increasing a student’s reading level and supporting them to graduate high school could provide an increased quality of life, which in turn benefits everyone that calls Saskatchewan home. Living without a completed high school education can be a significant barrier to attaining employment and places an individual in a life-long struggle for security of their basic necessities.[50]

“The content of the items in assessment tools that have been developed and normed predominantly on children of European-heritage in urban settings may reflect concepts, perspectives, and values that are unfamiliar to northern Indigenous children … The assessment approaches may put the children in uncomfortable or upsetting positions (e.g., being expected to provide immediate responses to questions, rather than being allowed the time to respond that is considered appropriate within the children’s culture).”[51]

The Saskatchewan Ministry of Education’s 2020-2021 Annual Report outlines efforts to create an improvement in the three-year graduation rates for Indigenous students from 35% to 65%. However, the report does not include details as to how these outcomes are expected to improve or confirmation of achieved improved outcomes. Without addressing systemic concerns related to education inequity for Indigenous students and Indigenous students with reading disabilities, a significant percentage of students may not receive the help and support they need leaving them to struggle throughout their educational experience. Addressing the ways in which reading is taught and supported from the earliest grades may yield long-term benefits (for all students), with the goal of improving graduation rates.

The Ministry’s Inspiring Success: First Nations and Métis PreK-12 Education Policy Framework cited The Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s Calls to Action, including progress in the area of reconciliation outlined within Goal 1.[52] However, the report does not directly address funding issues that may lead to better outcomes for students with reading disabilities (Calls to Action 8 and 9) which directly discuss academic funding, reporting and outcomes. Overall, the report contains limited information relating to reading levels and literacy of Indigenous students in Saskatchewan, both on and off reserve.

Within the Government of Saskatchewan’s Inspiring Success Framework, it states that by June 2020:

“Children aged 0-6 years will be supported in their development to ensure that 90 per cent of students exiting Kindergarten are ready for learning in the primary grades.”[53]

There is no clarification offered as to what constitutes “ready for learning in the primary grades” and whether this includes grade level comprehension of key skills that assist with learning how to read in Grade 1 and beyond, or what supports will be included and developed. Upon review of the 2023 Provincial Auditor of Saskatchewan’s Report (Vol. 1), we found that the conclusion and understanding of the Inspiring Success Framework to be:

“We found none of the goals within the Framework indicated how or when the Ministry plans to measure its success. Having measurable goals helps organizations monitor progress an whether changes are needed.”[54]

This conclusion of the Inspiring Success Framework is shared by the Saskatchewan Human Rights Commission as it has failed to provide direction demonstrating how the Ministry plans to achieve the five goals outlined within the Framework, including how they will be measured and evaluated. As previously mentioned, the Saskatoon Public School Foundation’s 2020-2021 Annual Report and 2016-2017 Annual Report state that each year, 28% of students in Saskatoon schools have not met Grade 3 level reading standards.[55] While the statistics vary for location, there appears to be a gap in learning outcomes that takes place between Kindergarten and Grade 3, with consistency of reporting and data collection also being a barrier to program improvement and evaluation.

The Saskatchewan Auditor also recommended that the Ministry of Education change their evaluation processes and focus to more than just graduation rates and student achievement starting at Grade 10. To create the best outcomes and evaluate ongoing efforts to improve Indigenous student achievement, it recommended evaluations begin prior to Grade 7, potentially decreasing the number of students that would have been struggling or have even left the school system by Grade 10.[56]

“When students read at grade level, it helps set them up for educational success in other subjects. The Ministry and school divisions identifying key educational outcomes (like reading levels) where Indigenous students are falling behind is imperative to making improvements early enough in their learning path.”[57]

In 2016-2017, 14.4% of students enrolled in Saskatchewan’s Kindergarten classrooms were either First Nations or Métis. The majority of Indigenous students (74.8%) attended off-reserve schools in the 2016-2017 school year.[58] Saskatchewan’s Indigenous population is predicted to rise significantly over the next decade, to 240,000 people or 24% of Saskatchewan’s total population by 2031.[59] As shown earlier in this report, Saskatchewan based data from the 2019-2020 academic year shows that only 55.5% of First Nations, Métis and Inuit students are meeting Grade 3 level reading, writing and mathematics standards as compared to an overall average of 75% of students meeting grade level.[60]

This data demonstrates a massive gap in academic achievement between Indigenous and non-Indigenous students that needs to be actively addressed. It does not however, provide relevant information as to the percentage of Indigenous students that may or may not have reading disabilities, or where they attend school. This information could be used to inform the needs and next steps of those working to address reading disabilities and literacy rates within Indigenous communities in Saskatchewan.

With the expected growth of the Indigenous population, this issue requires immediate attention to lessen the number of students and families affected by reading difficulties and reading disabilities. Concerns related to on-reserve education, isolated and rural schools, and schools where Indigenous children are the majority should be seen as a priority to adequately address ongoing equity gaps. The Commission recommends a strong focus on collaboration with Indigenous communities, Indigenous experts in the area of reading and teaching and Indigenous families in order to address these concerns and align with the Truth and Reconciliation’s Calls to Action number 10, in particular.

Student and school access to Jordan’s Principle

One option for Indigenous families to access educational supports such as the need for a psycho-educational assessment in a timely manner, tutoring support, assistive technology and supports among other things is Jordan’s Principle. Jordan’s Principle, created in honour of Jordan River Anderson, is a child-first principle that aims to eliminate service inequities and delays for First Nations children.

The purpose and benefit of Jordan’s Principle is that it provides access to any public service that is ordinarily available to all other children and, therefore, must be made available to First Nations children without delay or denial, meaning the process to apply and receive the necessary educational supports can be faster than waiting for Saskatchewan’s education systems to provide them.

While Jordan’s Principle is an option for Indigenous families that qualify for funding, our survey results indicate that only one participant accessed and received support for the cost of a psycho-educational assessment that was not completed in-school due to the waitlist for the assessment was seen as too long by the student’s parents. Schools have also accessed Jordan’s Principle to provide assessments and ongoing supports in a timely manner.

While this has been approved for many schools on a regular basis, it highlights the need for more adequate funding in order to provide these resources to schools and students without having to access outside options such as Jordan’s Principle for things that should be considered a necessity of any school within Saskatchewan. Not all schools are willing to go through the application process to access needed resources from Jordan’s Principles, serving to further inequities within our education system and society as a whole.

Reconciliation

It would be remiss to not acknowledge the importance of reconciliation and the value that has been placed on education within the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada’s 94 Calls to Action. The Calls to Action dedicate an entire section of their report to Education and the amendment of current practices and areas of concern for Indigenous children. It is appropriate to quote the relevant sections which refer to the educational concerns of Saskatchewan’s Indigenous children and the ways that can serve to create better experiences for all students and work towards meaningful reconciliation:

Education [61]

6. We call upon the Government of Canada to repeal Section 43 of the Criminal Code of Canada.

7. We call upon the federal government to develop with Aboriginal groups a joint strategy to eliminate educational and employment gaps between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Canadians.

8. We call upon the federal government to eliminate the discrepancy in federal education funding for First Nations children being educated on reserves and those First Nations children being educated off reserves.

9. We call upon the federal government to prepare and publish annual reports comparing funding for the education of First Nations children on and off reserves, as well as educational and income attainments of Aboriginal peoples in Canada compared with non-Aboriginal people.

10. We call on the federal government to draft new Aboriginal education legislation with the full participation and informed consent of Aboriginal peoples. The new legislation would include a commitment to sufficient funding and would incorporate the following principles:

i. Providing sufficient funding to close identified educational achievement gaps within one generation.

ii. Improving education attainment levels and success rates.

iii. Developing culturally appropriate curricula.

iv. Protecting the right to Aboriginal languages, including the teaching of Aboriginal languages as credit courses.

v. Enabling parental and community responsibility, control, and accountability, similar to what parents enjoy in public school systems.

vi. Enabling parents to fully participate in the education of their children.

vii. Respecting and honouring Treaty relationships.

“Along with high-quality, evidence-based instruction on early foundational reading skills, First Nations, Métis and Inuit students need holistic approaches to learning and high-quality learning environments that are consistent with Indigenous world views. Educators need to connect with local First Nations, Métis and Inuit communities to find ways to incorporate their experiences and values throughout classroom content.”[62]

4. Survey Results

The Commission gathered information about students with reading disabilities in the education sector. This included reviewing recent academic research and reports from Canadian jurisdictions.

As a stakeholder-based process, the systemic investigation gathered stakeholder perspectives, lived experience, and commentary. This occurred through interviews and two surveys. The interview conversations all occurred via videoconference. This work began in July 2020 and consisted of one-on-one or group discussions with more than 49 individuals and organizations. These conversations typically took the form of a free-flowing discussion based on a common set of questions. Participants were selected based on personal and/or professional experience, expertise and decision-making authority related to the topic of students with reading disabilities.

The two surveys were completed online by persons who self-selected, or chose, to participate. The surveys were disseminated by various stakeholder organizations to their individual networks. For the Parent/Student Survey, 183 people chose to provide information about their experiences and observations. The second survey, designed to be completed by educational and medical professionals, received 293 responses.

Stakeholders Observations and Experiences

Participants provided both qualitative and quantitative data. This included detailed information about direct and personal experiences. While individual experiences varied considerably, there were areas of significant overlap and agreement. On several topics, themes emerged from the discussion where different stakeholders recounted similar experiences or observations. These themes are distilled into topics and sub-topics below.

The selection of quotations throughout this section of the report were selected from interviews or from survey comments to highlight aspects of the aforementioned common themes. They were provided by stakeholders on a confidential basis. Often, the particular sentiment or point expressed was repeated by more than one participant.

Impacts on Students/Parents

When students have difficulty learning to read, it can negatively affect their confidence, their academic abilities, and their overall self-esteem. This, in turn, may lead to significant mental health concerns.

In the Parent/Student Survey, numerous parents provided the Commission with stories about how their children felt “stupid” and were often teased or ostracized because of their reading disabilities. Many said this resulted in high levels of stress and anxiety.

There has been unending stress and a large emotional toll on our child, with significant damage to his mental health and self-esteem.

In school [our son] feels stigmatized. Does not enjoy school at all. Feels different all the time.

A few students, who have since graduated from the K-12 system, reported similar experiences and described their lasting effects.

The emotional trauma from school even now, two years out of it I am still unravelling The damage. When I look back at some of the experiences I automatically almost have a panic attack just thinking about it. The stress of being in a science class when I have a severe learning disability in reading in writing that I can hardly pick up a book … that kind of stress shouldn’t be added onto the normal stresses of high school. (sic)

Constantly being stressed and in flight or fight mode for 12 years can leave scars deeper than you realize.

Of the parents surveyed, many said that having a child with a reading disability has created ancillary issues for the entire family. These issues range from heavy financial burdens to negative impacts on relationships and mental health.

Families who can afford private tutoring outside of school or fee-for-service learning programs reported investing substantial resources in helping their children learn to read.

The financial burden has been overwhelming for our family … It has cost us thousands in tutoring costs. Our son has to do hours of tutoring after school leaving him no time to socialize or have any enjoyable extra curricular activities because we cannot afford the money or time after the cost of tutoring.

Many families surveyed indicated they spend a great deal of after-school hours working on reading instead of spending time with friends and other family members.

It takes more time as a parent to sit with and assist the child with a reading disability to help them with their learning goals. On average this is done 5 times a week. When the child is young, it limits the amount of things they can do independently. We spend a great deal of time reading to our child every day.

We barely see our second child because we spend all our extra time helping our daughter do her school work.

Several parents told the Commission they have given up employment to have the time necessary to support their child in learning to read. Some have made the choice to drive to different towns or cities each day in order to send their child to schools with programs that specialize in reading disabilities.

We have had to remove our son from public school and take him to a private school that specializes in teaching kids with dyslexia … He now goes to school in a completely different town then our other son and this is a real struggle to facilitate. We as parent now need to drive over two hours every day to get our son to and from school this takes away time money and energy from the rest of our family.

Parents of children with reading disabilities reported experiencing significant stress and anxiety, as well as guilt, fear, shame, helplessness, frustration, disillusionment, and isolation.[63] This can cause tension in relationships between parents, affect mental health, and have further impacts on family dynamics. Many of the parents surveyed noted they expend significant time, money, and emotional energy trying to get help for their children.

As a parent I have to see a psychologist because of the emotional trauma I went through trying to get my son help.

This is a heart wrenching process to go through. It causes years of pain for both the students and the families … I have put in everything I have emotionally and finically (sic) into this struggle but it has been hard to do it year after year.

System Navigation

The Commission heard from numerous parents who experienced problems navigating the education system in search of help for their children. For some, these difficulties arose at the very start of the process.

In the beginning, I didn’t know where to go for help. I had to find our way through the system with no help from the school system. In fact, they often increased my stress by telling me I needed to accept that my son would never learn to read & that he wouldn’t be able to graduate with a regular high school diploma.

Even for stakeholders who had a general idea of how to navigate the system, many said that obtaining the proper supports at the proper time was still a lengthy and cumbersome process.

… in my experience the children that NEED intervention normally do NOT receive it immediately. There are so many hoops, paperwork, applications and tests that the students … do NOT receive intervention until well after the 5th month of school. There are many students left behind.

To ensure students are not being left behind, parents felt they had to battle and advocate non-stop to have their children’s needs met.

My son and our family have been greatly affected by his reading disability mainly because we had to fight for everything he currently has and continue to do so every semester.

Our experience is horrific. I wish it was a one-off and not the norm, it isn’t. My son continues to struggle through the system, our trust and faith in the education system is gone. We advocate and fight for every accommodation.

The Commission also heard that this ongoing struggle in navigating the system can, at times, be compounded by external factors. One parent reported that the process of obtaining support for their child has been exacerbated by their own reading disability.

It is a constant battle to get the necessary support, as a dyslexic myself navigating the information and internal self-doubt from my own time in the school system, was incredibly hard. There are so many barriers that families face when their child is diagnosed with a learning disability that impacts reading and writing and most of them are completely preventable.

General reactions from the surveys show that there appeared to be a direct relationship between a parents’ ability to advocate and access resources (often private resources paid for out of pocket) and the ability of a child to receive proper supports. Without parental advocacy and pressure, in many cases, support was not offered or had continued to be refused due to each school’s limitations or behaviours that disqualify children from receiving adequate support and intervention such as not being seen as a disturbance in class.

Some parents who participated in the survey also mentioned they were unsure as to the general details of their child’s accommodations, were not provided concrete information or updates and, in several cases, the child was given assistive technology without any individual or ongoing reading and learning support.

In these instances, parents feel better collaboration and communication between all parties is required.

Screening

A screening measure is a quick and informal evidence-based test that provides information about a child’s development in a specific area, such as possible reading difficulties.[64] This is not the same as receiving a diagnosis. Screening can identify students who are experiencing reading difficulties for the purpose of being able to provide those students further intervention and support where needed.

Experts in the area of literacy and learning to read recommend that screening be done as early as possible with continued screenings until students should be expected to read with fluency.[65] And while the parents, educators, and medical professionals surveyed by the Commission tended to agree with this approach, many said that in Saskatchewan this is simply not the case.

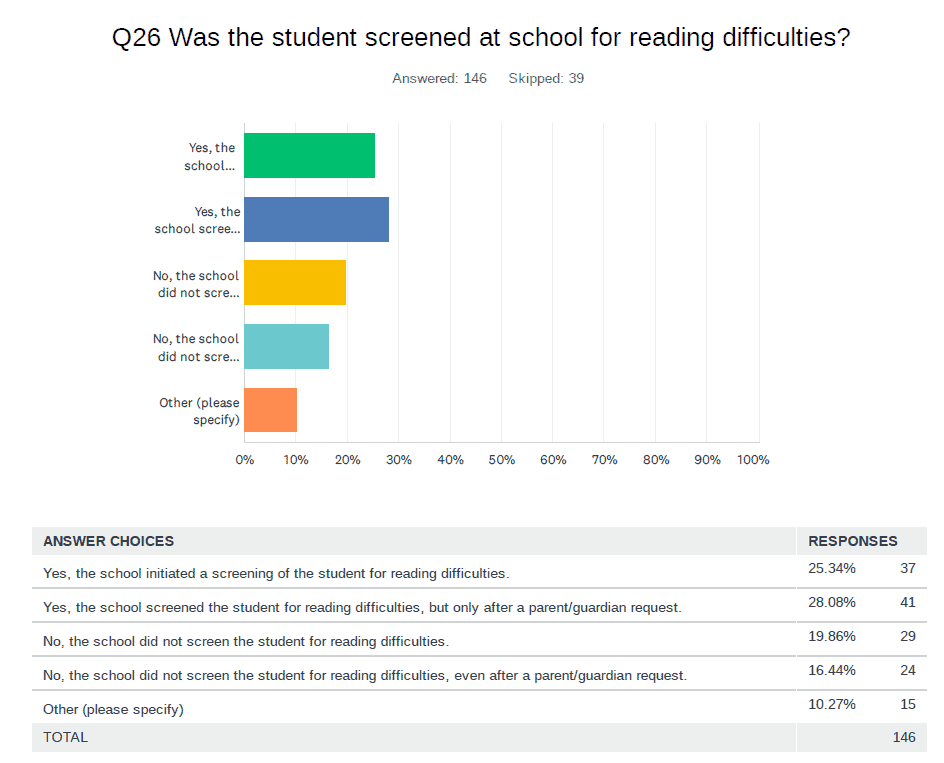

Some parents stated it was difficult to get their children screened at school. Of the 183 people who completed the Parent/Student Survey, 53% reported that students had been screened at school for reading difficulties. Half of those students were only screened after a parent/guardian requested it. (see Appendix A1)

According to professionals who completed our Education and Medical Survey, many of the problems associated with in-school screening arise because of insufficient resources.

Resources and lack of funding for Education have made it almost impossible to adequately screen all children for a reading disability at an early age (prior to grade 2). We know the importance of early detection and intervention but are unable to provide it to the extent required due to budget (and therefore personnel) limitations.

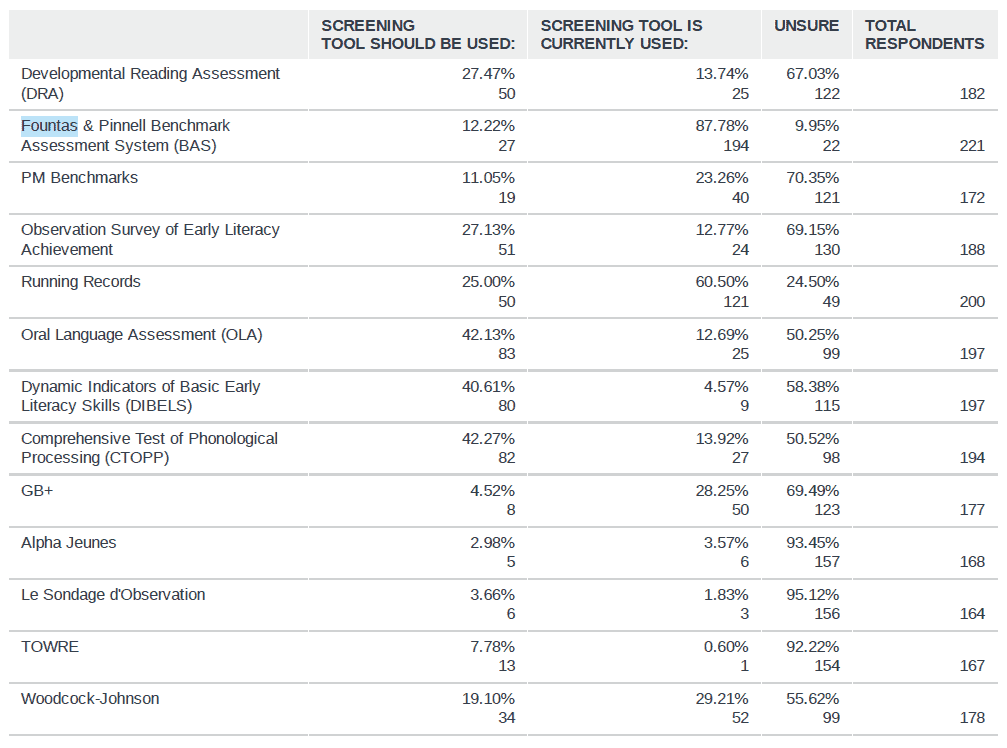

In instances where in-school screening does occur, screening tools vary.

Survey respondents indicated that along with screening tools, screening practices also vary between boards, schools, and even individual teachers. Many stakeholders believe it is time to reassess the way the education system screens students.

Classroom teachers do F&P but this does not reliably tell us who may be at risk for reading difficulties.

There should be a systematic screening tool used province wide to target struggling students and the results follow them if the student moves.

Early, Universal Screening

Universal screening involves conducting common, standardized screening assessments on every student using evidence-based screening instruments. These instruments have established reliability and validity standards to increase confidence in their effectiveness and should be grounded in scientific research and evidence.provided from a variety of sources, including experts in the area of reading disabilities.Cultural considerations and adaptations should also be included to ensure equity and reliability of the assessments.

One theme that was consistently reported by parents was how the “system is failing” children with reading disabilities in Saskatchewan. According to numerous professionals surveyed, one of the reasons this is happening is because many students are not being screened effectively or early enough.

Early screening for reading difficulties is not completed enough in our province.

We don’t have an early screening protocol, so I know we are missing many students who would benefit from early intervention. Our reading assessments reflect that too many students are reading below grade level. Students who do receive a reading intervention usually don’t get this until grade 2 or 3 and because they are ‘the weakest of the weak.

Early screening is a vital tool that we don’t have the funding or training to appropriately implement.

To make things more equitable, efficient, and effective, numerous stakeholders we spoke to stressed the need for early, universal, systematic, and evidence-based screening in Saskatchewan.

I wish early screening for reading difficulties was a priority and done with a science of reading model and evidence-based tools that measured more than just reading fluency and reading comprehension. I wish the tools gave teachers and schools better information to help struggling readers.

If anything, we should have universal screening for SLP even more now, then before, with interventions embedded into the kindergarten and grade 1 curriculum.

Ages four to seven are a critical window of opportunity for teaching children foundational word-reading skills and is when intervention will be most effective.[66] As such, it is important that students are screened early. It is equally important for these screenings to be universal with the possible inclusion of brief assessment relating to measure of attention.

Adopting the practice of early, universal screening for children in Kindergarten and Grade 1 could lessen the stress and urgency faced by those who struggle with learning to read, and then fall farther behind their peers and expected grade level of reading.

Following that with ongoing, adequate, and individualized intervention plans and accommodations that adapt with the child’s literacy and skill level would continue to reduce both barriers and impacts on the child throughout their educational career. Early, universally implemented screening – along with the necessary supports for these children – can also reduce the stigma faced by those with learning disabilities.

In addition, if implemented across the province, it would allow for better data collection to help inform decision making and equitable access regardless of geographical location.

From a human rights perspective, universally implemented screening – when used responsibly, in consideration of the diversity and demographics of the student community – is “necessary to protect the rights of all students, particularly students from many marginalized and Code-protected groups.”[67]

It offers protection by:

- Reducing the potential for bias,

- Facilitating early intervention, and

- Addressing the needs of students with both reading difficulties and disabilities.

Responding to Screening

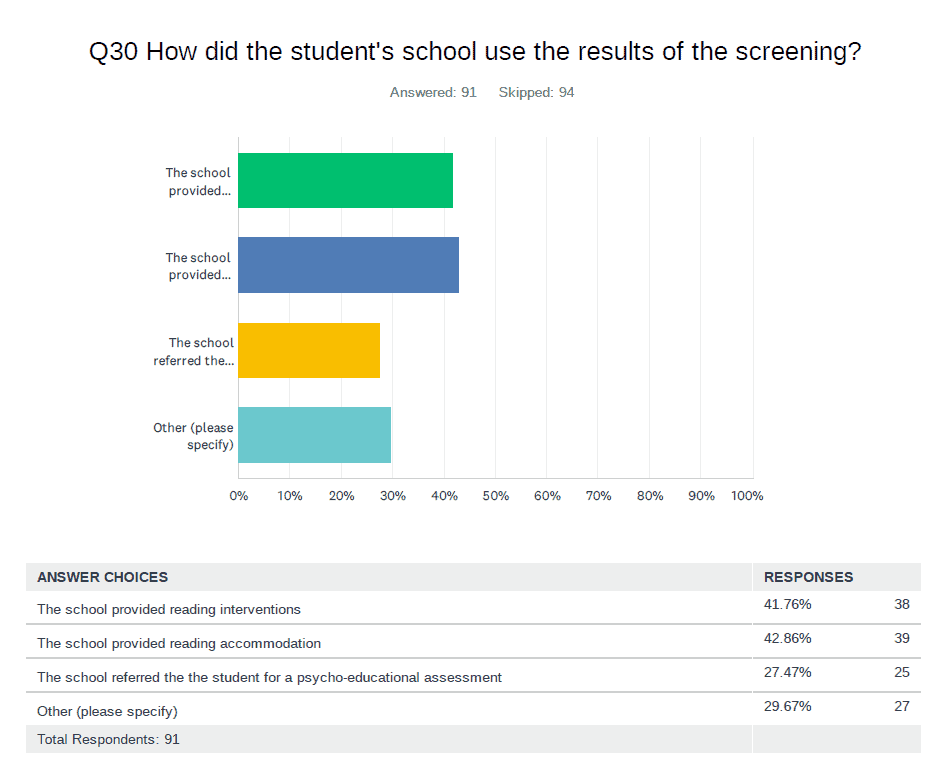

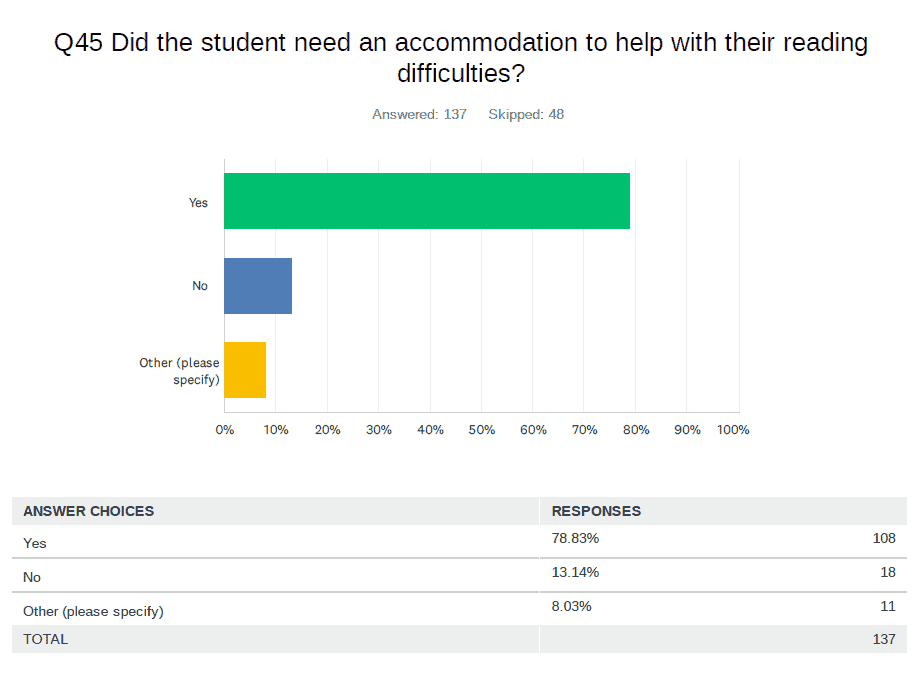

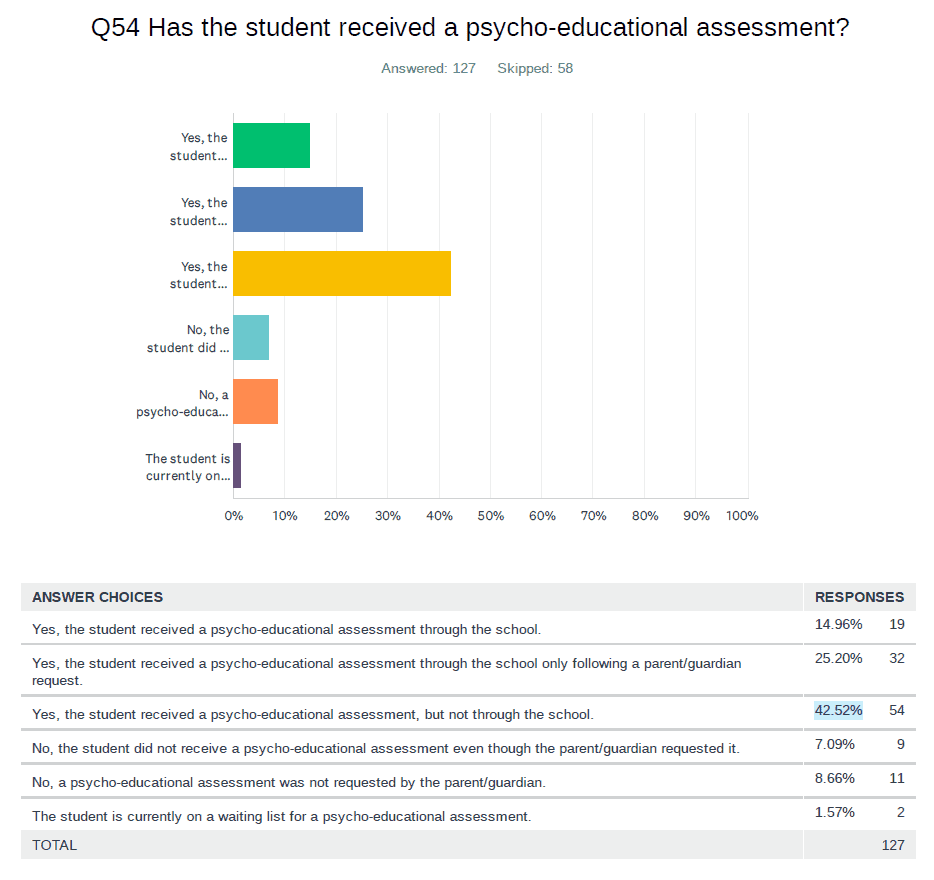

Another concern raised by parents and students who took the Commission survey was the way in which schools used the results of initial screenings. While approximately 42% of the respondents said the student received reading interventions and/or accommodations, only 27.47% said the student was referred for a psycho-educational assessment (see Appendix A3).

Some described the actions taken after the initial screening as insufficient, ineffective and, at times, detrimental to the student’s progress.

[Our child] was put in a reading program that did not address dyslexia.

They sent our child to “resource” which did nothing to build her self-esteem or assist her.

Didn’t have to enough people to help and eventually school didn’t provide help until I was in grade 12. Even then the teacher wasn’t trained to help me and it was just a quite place for me to do my homework.

Other parents reported no post-screening response whatsoever.

The school said there was nothing they could do.

Nothing happened. We switched schools in the same system but nothing ever happened.

Program Intervention

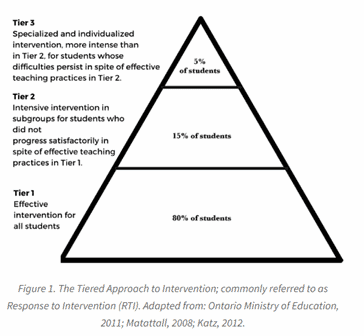

In the education field, including in Saskatchewan, Response to Intervention (RTI) is a widely accepted framework to support student success. RTI includes three tiers:

- Tier 1 – all students are taught core curriculum that is evidence-based and scientifically researched.

- Tier 2 – students whose knowledge and skills do not meet the expectations of Tier 1 instruction receive intervention in small groups with increased intensity.

- Tier 3 – supports for the very small percentage of students whose reading levels don’t meet the expectations of Tier 1 and Tier 2. These students are at a high risk of not learning to read. This tier incorporates more intensive use of Tier 2 intervention programs, or more specialized programs, often with smaller groups and more explicit instruction. (see Appendix A4)

In Tier 1 intervention, instruction for all students occurs in whole-class, small group and individual settings.

- The teacher knows his or her students, has developed positive relationships with them and created a supportive, nurturing environment that celebrates each student’s uniqueness.

- The teacher utilizes ongoing, authentic formative and summative assessment and the Saskatchewan curriculum to determine the needs of the student and differentiate within the instructional approaches.

- The teacher provides instruction designed to meet the specific needs of students in the classroom.

- The teacher uses the four high impact instructional approaches: modelled reading, shared reading, scaffolded/guided reading and independent reading.[68]

In Tier 2 intervention and instruction, students that have been identified through ongoing and frequent formative and summative assessment receive additional opportunities to improve comprehension, fluency and engagement.

- Once students have been identified a collaborative team approach is crucial to planning supports for students.

- Tier 2 intervention and instruction does not replace the instruction that happens in tier 1. Instead, it offers additional support so students can meet curricular outcomes. The intervention should align with the classroom instruction.[69]

A detailed description of Tier 3 was not able to be found on the Saskatchewan Reads website.

The move towards evidence-based pedagogies, proven to work with students that have and do not have reading disabilities, for core instruction (Tier 1), would mean that there would be less children classified as both Tier 2 and 3. This shift in instruction would provide more children with the explicit skills required to reach grade level reading and remain there. This would result in few children requiring Tier 2 and 3 resources, therefore making their instructional intervention more effective and efficient.

The sooner instruction can be improved, along with remedial action taken, the better the result. In this case, an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. Not addressing these issues at an early age will add to the difficulty and expense of assistance later in life and throughout a child’s academic career.

Research shows that the earlier children with reading difficulties receive effective interventions, the more likely they are to fully catch up to their peers in foundational reading skills that are essential for making continued yearly gains in reading.[70] Intervention is most effective when delivered in Kindergarten (or earlier in some cases), Grade 1, and no later than in Grade 2.[71]

Students that do not receive effective teaching and intervention from an early age are more likely to struggle as time goes on and require more intervention later to improve their grade-level reading. This process places undue hardship on students, their families, and those within the education system that want to see students succeed.

With science-based approaches to reading instruction, early screening, and intervention, it is estimated that Saskatchewan could expect to see only about 5% of students still below grade level expectations on word-reading accuracy and fluency.[72] Approximately 3-5% of students will have word-reading problems that are aren’t responsive to even effective interventions.[73]

This, however, isn’t the case in Saskatchewan.

Approach to Reading Interventions

A consistent theme the Commission encountered in our surveys and interviews with stakeholders had to do with an inadequate approach to reading instruction and intervention, particularly with students struggling with reading.

In general, educators we heard from felt there is a lack of – and dire need for – early, evidence-based reading interventions in the province.

Almost all reading interventions being used are not ground in the science of how reading is learned. I have had to come to this on my own – I did my own research and paid for courses to re-train myself as I was frustrated that the reading interventions I was using weren’t working … ALL of them followed balanced literacy and whole language. NONE had any grounding in the science of reading.

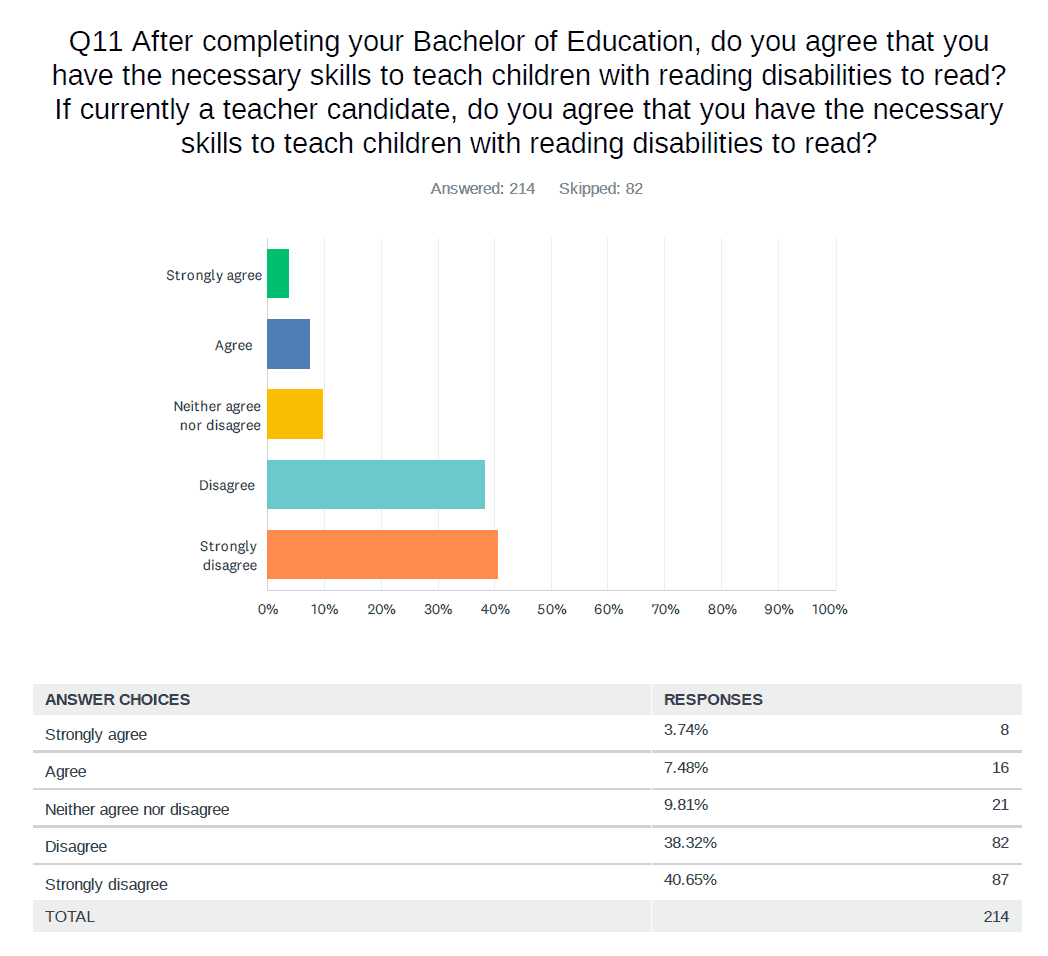

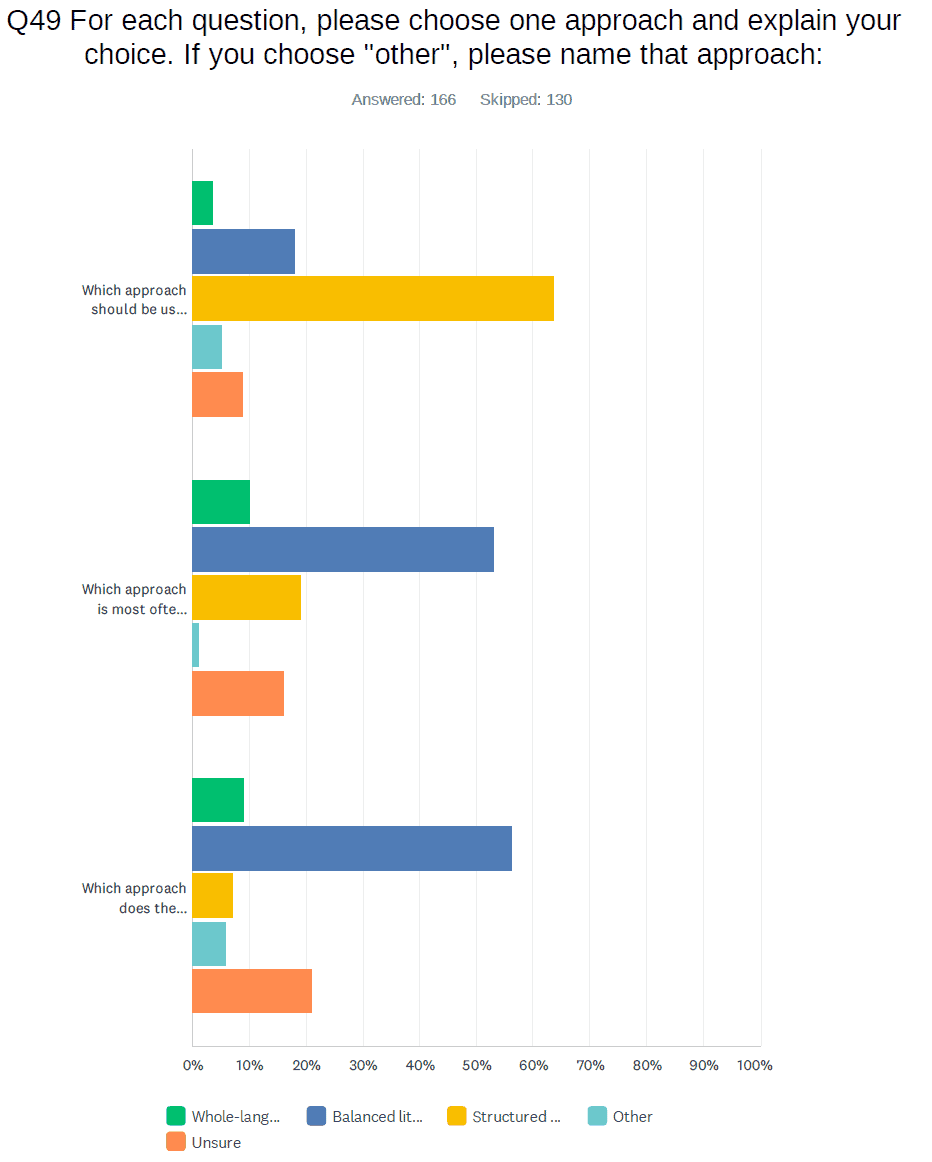

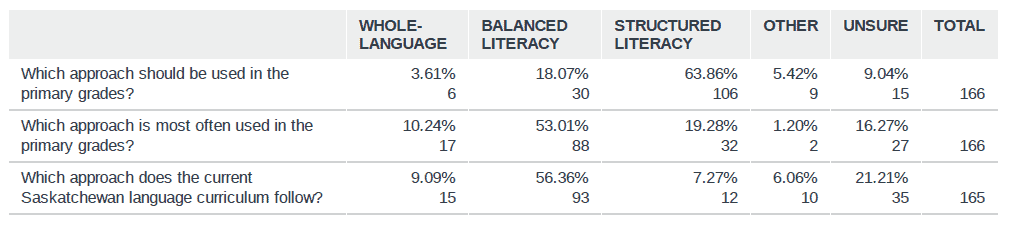

If classroom teachers followed a Science of Reading approach to tier 1 instruction, rather than a balanced literacy approach with incidental instruction, we might actually have enough time to meet the needs of students who needs extra.